Living conditions are increasingly difficult around the world due to global climate change. And climate change, as we have already written, does not just mean extreme weather conditions: the impact of rising sea levels, damaged ecosystems and environmental upheavals will cause global geopolitical imbalances.

Secondo UNHCR, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, in the decade 2008-2018 as many as 21,5 million people per year were displaced by meteorological events such as floods, storms, fires and extreme temperatures. Numbers that will increase in future years: the international think tank IEP estimates that 1,2 billion human beings they could suffer the same fate by 2050, and become climate refugees.

Who are the climate refugees?

The term “climate refugees” born in the 1985 and distinguishes people forced to leave their habitat, temporarily or forever, due to "environmental disturbances". The definition of the time, drawn up by the UN expert Essam El-Hinnawi, is already affected by the years and needs to be updated.

An example? In 2020, two Category 4 hurricanes hit Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador. People flocked across the Mexican border towards the US, having lost their homes, access to clean water and livelihoods due to landslides and torrential rain. “Environmental disturbances”, as the 1985 definition says.

Today the definition however, it must be extended to a much wider range of subjects, who do not always see a direct cause-effect relationship in the reason that makes them climate refugees. Often, and increasingly, climate refugees will depend not on “disturbances” but on structural changes in the ecology of the planet.

Another example? Sea level rise. Over the past 30 years, the number of people living in high-risk coastal areas has increased by 160 million to 260 million. 90% of these come from developing countries and small island states.

A global domino effect

The situation is getting worse (or increasing our awareness, if you like) because climate risks are interconnected, and often cause chain reactions. If temperatures increase in a nation, for example, drought reduces incomes, food resources and exports. The cost also increases for other nations. There is a risk of epidemics, and of changes apparently unrelated to that circumstance.

Take Syria: between 2006 and 2010 a good number of fertile lands desertified. The harvests have shrunk, 800.000 people lost their livelihoods, 85% of Syrian livestock died. Result? Dizzying increase in prices, 1.5 million climate refugees from the countryside in the city, and those who remained in rural areas have become easy prey of the Islamic State.

Do you understand the connection? From the environment to civil wars, everything can be part of a single domino effect. Which produces (as in the case of the Syrian war) other refugees: many refugees. 25% of Syrians, over 6 million people, have fled the country.

How should they be considered? Climate refugees or political refugees?

There is a high correlation between countries that are particularly sensitive to climate change and those that are experiencing unrest or bloodshed. According to the UNHCR Global Trends in Forced Displacement 2020 study (I link it here), 95% of all displacements due to conflicts in 2020 occurred in countries that are vulnerable or extremely vulnerable to climate change.

We need to recognize climate refugees as a problem that can have significant implications for international security, instability, conflict and geopolitics. And we need strategies that allow humane, safe and proactive management of climate migratory flows.

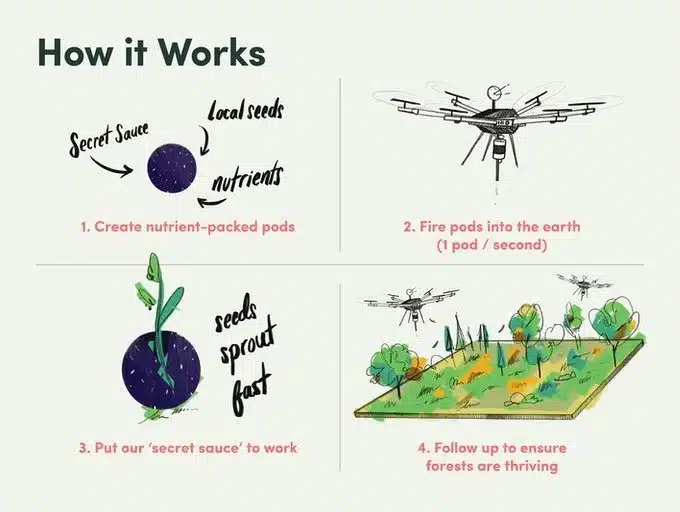

Science and technology play their part. Floods have increased in Bangladesh the salinity of agricultural land by 53%. Farmers, in short, are no longer able to grow their normal crops. A Dutch research project called The Salt Solution aims to convert their crops into others more suited to the changed conditions. Among these: potatoes, carrots, cabbage and coriander. So far 10.000 farmers have received training, resulting in two to three extra crops a year. Same objective for the research project financed by 7 European countries and called Salfar (Saline farming) we talked about here. Help could also come from drones (land o steering wheels) capable of planting trees and rapid crops, also fighting desertification.

Other things needed? A special status for climate refugees, an inter-agency working group to coordinate efforts worldwide, and all the other good ideas that come to mind.

However, the best help for climate refugees is elsewhere.

The ultimate solution (also to the problem of climate refugees) is to achieve at all costs the objectives set out in the Paris Agreement to limit temperature increases to well below 2 degrees Celsius (°C) and ideally to 1,5° C. We have very, very few chances of making it if we don't move now.

We must act collectively to manage this crisis. It takes tremendous teamwork, from governments to civil institutions, academia and businesses.

Even as individuals, we must carefully consider our responsibilities as consumers, voters and global citizens. Together we can make a big impact. But we must hurry!