If I tell you "Kraft Heinz” surely something comes to mind. Could it be ketchup? Will it be Plasmon, or Philadelphia? It could be anything: it's a company that owns nearly 200 brands. Condiments, dairy products, meats, soft drinks, coffee: you can only imagine how extensive the activities of this mega industrial group are. And you can imagine how much its position, as a producer of processed foods, is at risk in an era that sees the rise of ever-increasing awareness of the fact that they are literally toxic. For this, KraftHeinz understood that it had to launch into a battle to obtain products with less calories, sodium, sugar and saturated fat.

“Especially sugars,” he says John Topinka, Head of Research Strategy at KraftHeinz.“We need to drastically reduce them by 2025 ".

You need to work hard

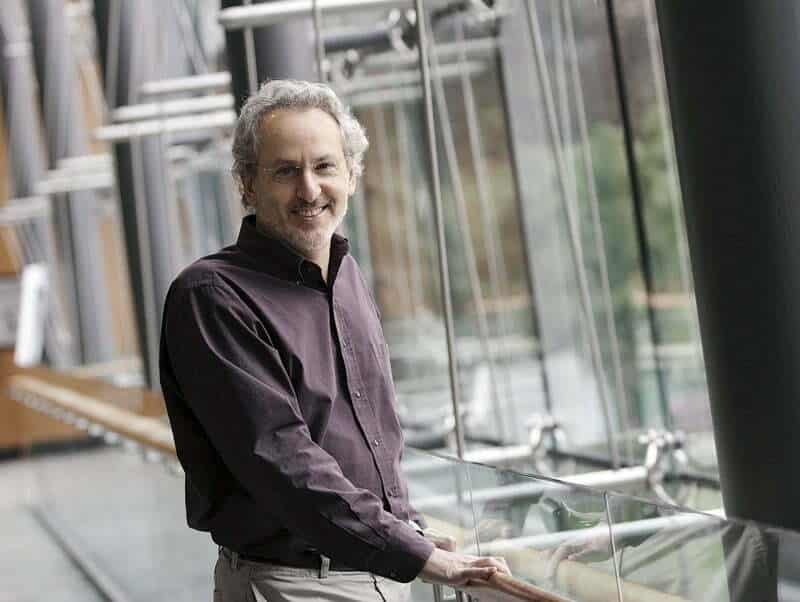

KraftHeinz already entered into a partnership with the in 2018 Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering from Harvard, an institution that uses biological design to create new solutions. The target? Develop new techniques and technologies to reduce the sugar content in their products without compromising taste. And it's frighteningly difficult stuff, because sugars don't just provide sweetness. They provide browning in baked goods (with caramelization), the thickening of spreads such as jams and preserves, the creation of an acidic environment to prevent food spoilage, and other elements. To that question, to KraftHeinz's surprise, Wyss founding director Dr. Donald Ingber, responded with another question:

Is creating a sugar substitute really the best approach? What if we worked on the effects of sugar on the body?

It was the beginning of an enormous research activity, with a new objective: not to eliminate sugars, and perhaps not even to reduce them. Make them healthier.“We thought we came to Wyss with an impossible problem, and they turned it around with an even crazier idea to solve it, says Judith Mocha, Head of Technology Discovery and Development at KraftHeinz.

Sugars that are good for you, impossible. Or not?

The Wyss team led by Don Ingber, Jim Collins, David Walt e Dave Weitz, chose to play the card of some enzymes present in nature: enzymes used by plants to transform sugars into fibre. These enzymes could be added to foods without changing their sugar content or sweetness, but converting them into fiber once in the gut. You understood correctly: not only would this technique reduce the absorption of sugars into the bloodstream, but it would also produce prebiotic fibers beneficial for intestinal health.

Fantastic idea, but purely theoretical. “We didn't just want our solution to be technically sound,” explains Dr. Adam Sesay, senior engineer and member of the team that oversaw the project. “We wanted it to actually be able to work in the reality of food production. After all, what good is a solution that only works in the laboratory?”. Eh. Indeed.

And so?

4 years after the start of the research, we don't know if the path is the right one. However, we know that the Wyss team has successfully developed this enzyme. And this enzyme can be added to existing food products without having to modify the recipes: it remains intact during industrial food processing, even at high temperatures. How did he do? Using encapsulation methods to ensure that the enzyme remains intact until exposed to an increase in pH, such as that which occurs in the transition from the human stomach to the intestine, where it becomes activated and begins to convert sugar into fibre.

But does it work then? The simple answer is: yes, it works. The complex answer is: it's not enough that it works. Its long-term effects on a human organism, digestion and other elements must also be evaluated. For this reason, Ingber's laboratory is currently testing the enzymatic product on mice to evaluate its effects on dietary sugars in a living organism over time. The scientist then hopes to launch a start-up to sell this product to all food companies, not just Kraft Heinz.

That would be one of the sweetest news stories in history, don't you think?