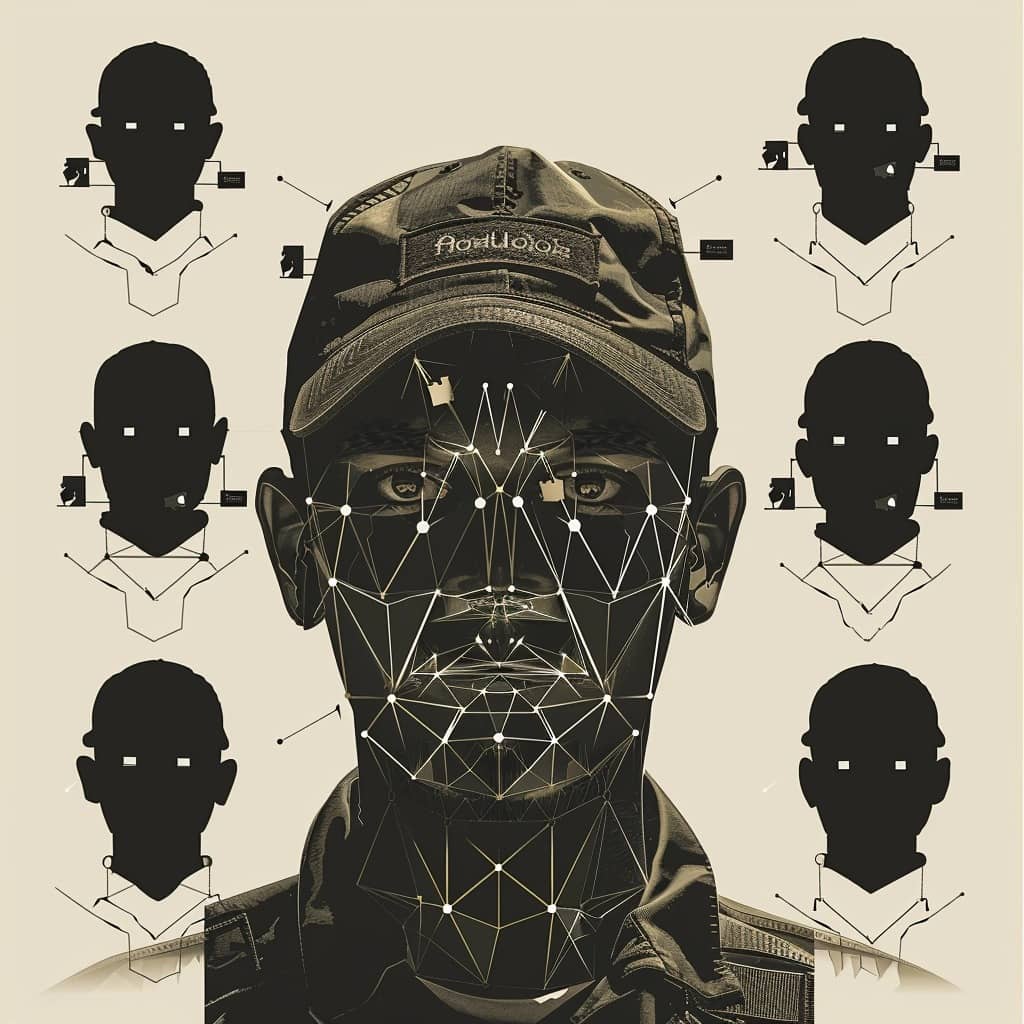

Facial recognition technology can be a powerful tool for ensuring security, but also a dangerous weapon if used in an opaque and discriminatory way. This is demonstrated by what happened in the Gaza Strip, where Israel quietly implemented a vast biometric surveillance program on Palestinians following the atrocious and barbaric attacks of October 7. Leveraging the algorithms of Google Photos and the startup Corsight, the Israeli army has profiled thousands of people without their consent, in what appears to be a disturbing case of high-tech ethnic profiling.

Big Brother in Gaza

The story, reported by the New York Times, has the contours of a dystopian thriller. After the October 7 attacks, the Israeli army's Unit 8200 (the main intelligence unit) began identifying potential suspects by analyzing surveillance camera images and videos that Hamas had posted on social media. At the same time, soldiers interrogated Palestinian prisoners to identify people from their communities affiliated with Hamas.

With this material, the startup Corsight (which boasts systems capable of recognizing faces even when less than 50% of them are visible) has built an ad hoc facial recognition tool for Israeli officers working in Gaza. To further enrich the database and find other targets, the military installed checkpoints equipped with biometric cameras along the main roads used by Palestinians to flee to the south. The goal, an official revealed to the Times, was to create a “hit list” of participants in the October 7 attacks. In practice, a file of the "usual suspects" based on algorithms and ethnic profiling. A hi-tech manhunt, conducted without the knowledge and consent of those involved. An Orwellian nightmare come true.

Israel, errors and abuses

Technology, as we know, is not infallible. Especially when it's based on grainy images or partially covered faces. This is also why Europe has a rightly cautious approach towards facial recognition. Israeli soldiers themselves admitted to the Times that Corsight's system was not always accurate. He sometimes falsely identified people as affiliated with Hamas. This is the case of the Palestinian poet Mosab Abu Toha, picked up from an Israeli checkpoint as he tried to leave Gaza for Egypt with his family in mid-November. He had been reported by the AI as wanted. Result: two days of detention, beatings and interrogations, before being sent back to Gaza. Without even explanations.

A fate that could have befallen who knows how many other innocent people, labeled as potential terrorists only because of their ethnicity or the place where they live. A risk inherent in facial recognition systems, which can amplify human prejudices if not used with caution and transparency.

Google, the big ear

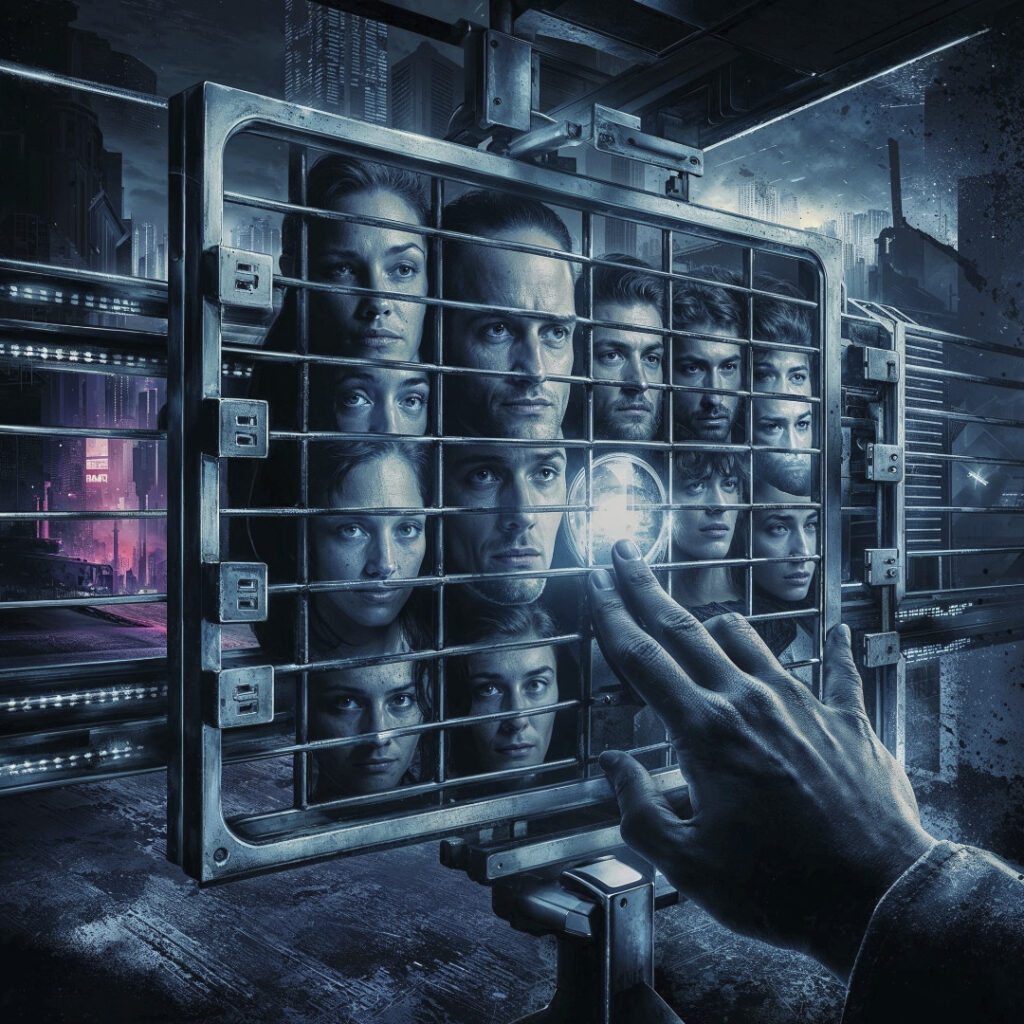

But it's not just Corsight behind this surveillance program. The soldiers revealed to the Times that the Israeli army has integrated the company's technology with another, more accessible and perhaps even more powerful tool: Google Photos. Intelligence officers uploaded “known person” databases to Big G's servers and used the image search function to identify additional suspects. Google Photos, a soldier observed, is able to recognize faces even from minimal details, surpassing other applications, including Corsight.

In short, the Mountain View giant, perhaps without knowing it, has become a key cog in Israel's control machine over Gaza. A great ear capable of mapping and spying on an entire population, violating their privacy and rights in the name of national security. A controversial and opaque use of AI, which in Gaza is combined with the use of other advanced technologies such as robots and drones, and raises questions about the ethical responsibilities of big tech.

Not just Israel: the dark face of surveillance

Unfortunately, the case of Gaza is not isolated. Corsight, founded in 2019 with an investment of 5 million dollars from the Canadian fund Awz Ventures, it specializes in the provision of facial recognition solutions. For a lot of realities: governments, law enforcement and armies. in 2020, just a year after its creation, the company boasted that it could identify masked faces. Two years later, in 2023, announced that it was developing a tool capable of reconstructing a person's features from their DNA (we talked about it here). in 2023, collaborated with the Bogota police to track down murder and theft suspects on public transport.

A growing business, fueled by the rhetoric of fear and the hunger for security, but not without gray areas. Just think of the statements of Aaron Ashkenazi, managing partner of Awz Ventures, who in an editorial last October in the Jerusalem Post he wrote that his fund was providing Israel with “the technological tools to stop these evil terrorists in their tracks.” It's easy to imagine what these tools are.

On the side of Big Brother

More generally, that of Corsight and other similar companies seems to be a mission in the service of global Big Brother. An effort to make every face traceable, catalogable and surveilleable, in a world where anonymity is a luxury we can no longer afford and privacy an optional to be sacrificed on the altar of defense.

It is therefore not surprising that in recent months some hospitals in Israel have also have started using Corsight algorithms to identify disfigured patients, as reported by Forbes. An apparently humanitarian application, but which paves the way for more questionable uses of this invasive technology. The risk, as the events in Gaza demonstrate, is that facial recognition systems become instruments of oppression and discrimination in the wrong hands. That they transform the right to security into an excuse to violate other fundamental rights, starting with the right to anonymity, or to a fair trial. Let's be clear: this is not about demonizing facial recognition itself, which can have positive applications in various fields, from healthcare to security. But to regulate its use in a clear and democratic way, placing limits on its potential distortions and abuses.

That reduce people to pixels and percentages, labeling them based on skin color, facial features or social background. A nightmare that certainly calls into question the responsibility of those who develop and sell these technologies, but certainly also of those who buy and use them.