Tobacco, fabrics, street smells: researchers embark on collecting and reconstructing an encyclopedia of perfumes (and more) from the last five centuries in Europe.

Apart from Proust, whose game was achieved by eating a Madeleine, for many of us, smelling a perfume or smell means traveling through time. The smell of wet earth reminds me of late August in my summers as a boy. That minty scent reminds me of the gummies in my grandparents' house. Odeuropa perhaps for this reason. Rebuilding time.

Of all the senses, smell is the most evocative of memories

Unlike photos (sight) or artifacts (touch) that we can keep in books and museums to record history, we cannot bottle a particular perfume and keep it forever.

The smells of the past are gone forever. Or maybe not?

Odeuropa, daily olfactory life

A research team has just launched an ambitious project to identify and reconstruct the most popular perfumes of everyday life in Europe, from the 16th century to the beginning of the 20th.

The project, called “Odeuropa”, is led by a multidisciplinary group of scholars from six European countries. Their specialties include history, art, computer vision, museology (the study of museums), and chemistry.

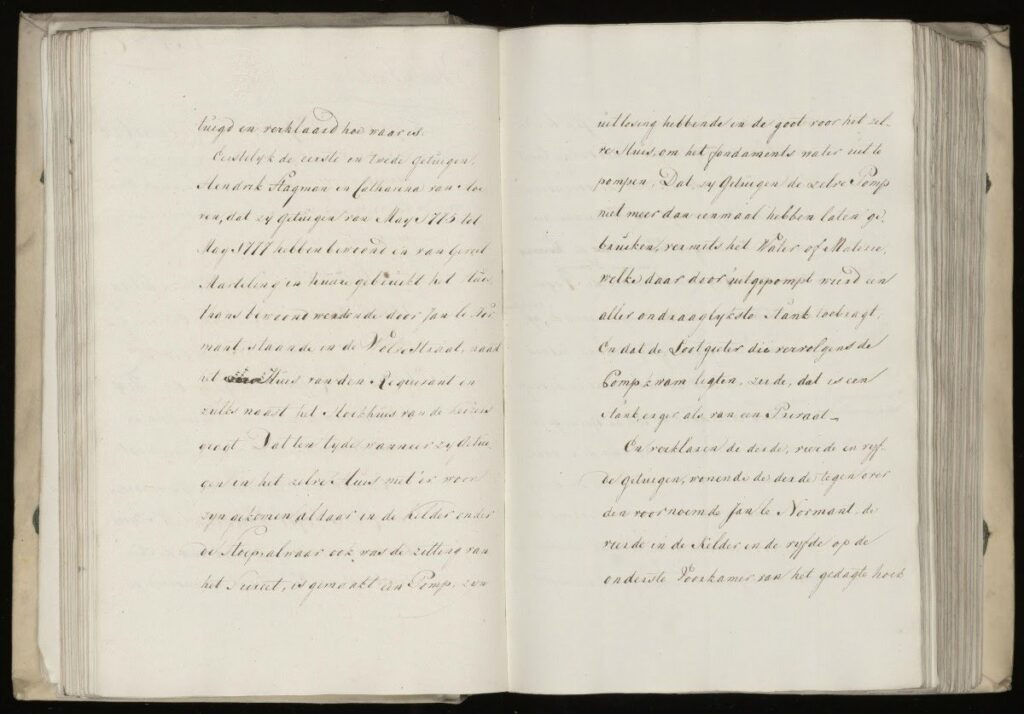

Using machine learning and artificial intelligence, the Odeuropa team will train computers to sift through endless periodic resources (textbooks, novels, photographs and magazines) to find references to smells, such as tobacco or perfume, in text and photos.

“Once you start looking at printed texts published in Europe since the 1500s, you'll find lots of references to smell, from religious scents like the smell of incense to things like tobacco,” says the team member William Tullett of Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge.

An encyclopedia of smells

The information will be cataloged in an "online encyclopedia of olfactory heritage". The project website describes the encyclopedia as “an archive for Europe's olfactory heritage, allowing future generations to access and learn about the smells of the past”.

One of the objectives, as mentioned, is to tell time through smells. Show how smells and their purpose and meaning have changed throughout history.

Take tobacco, for example. “It's a commodity introduced to Europe in the 16th century that starts out as a very exotic type of smell, but then quickly becomes domesticated and becomes part of the normal olfactory landscape of many European cities,” Tullett says.

Odeuropa is not the first modern attempt to capture the history of smell.

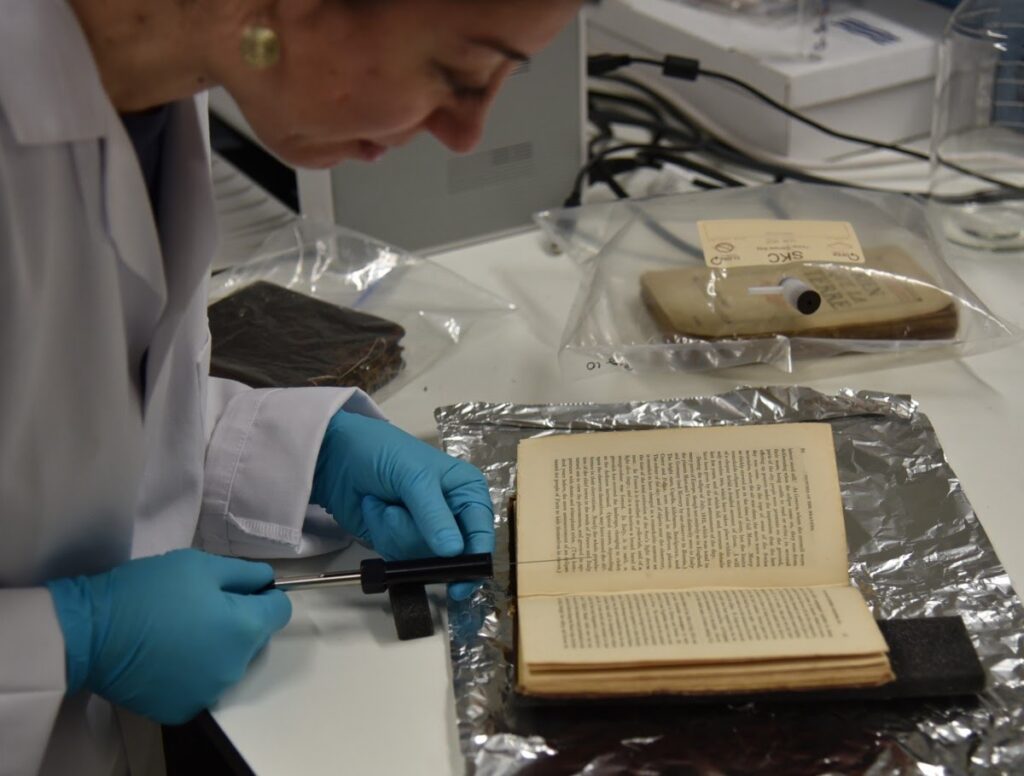

Kate McLean creates “smell maps” that record areas with strong odors, mapping cities like New York and Boston. Cecilia Bembibre, a researcher at the UCL Institute for Sustainable Heritage, is working on the recovery and conservation of lost or endangered perfumes.

Odeuropa has this and other purposes. He wants to have the ability to recreate smells that don't exist today. The project is expected to take three years to complete.

Thanks to this olfactory resource, perfumes that are now distant will be given new life, and become an important part of museum exhibitions or historical sites.

“Smells shape our experience of the world, but we have very little sensory information about the past,” he established Inger Leemans (VU University and the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts & Sciences Humanities Cluster).