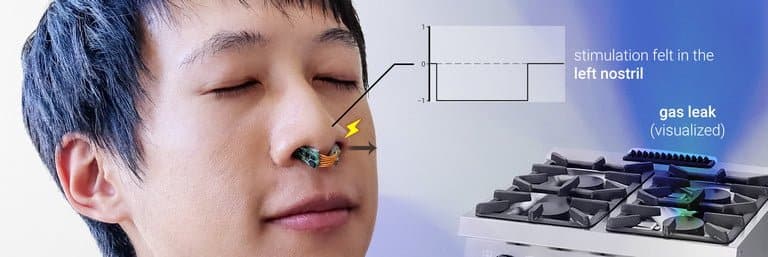

Jas Brooks He's an engineer who looks halfway between a rocker and a hippie. One day, Jas sat blindfolded in a room with electrodes in his nose, a sort of ring, and let people remotely “raise” his smell level.

This sounds like downright awful stuff. At least put it that way. It reminds me of theMilgram experiment (do you know him)?

In 1961 Stanley Milgram started a social psychology experiment that aimed to understand how people were able to obey orders contrary to their ethics. Participants were tested on their willingness to deliver electric shocks to participants.

As in the Milgram experiment (indeed, more: in that case they were only pro forma), Jas Brooks received small electric shocks from the people in charge of the experiment. No electroshock, however. Just sensations. Similar things to what you feel when you smell wasabi or vinegar.

Smell of the future

“It wasn't painful,” Brooks says. “I was sitting there picking up these 'smells'. I had the blindfold on, and the others had a panel with a drawing of my nose and two buttons, one in each nostril, with which they tested the sensor".

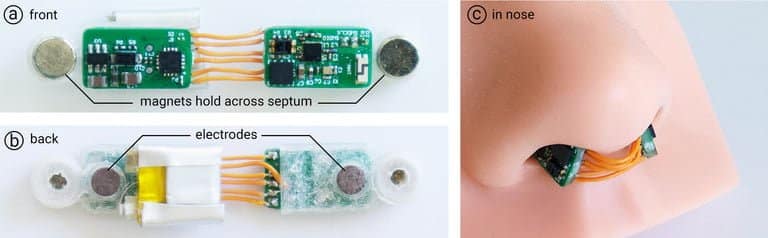

Brooks, a PhD at the University of Chicago Human-Computer Integration Lab, is focused on the shape of the technology to come. And, at least based on this recent experiment, one form the technology could take is a sort of magnetic “ring” that you put on your nose, which produces odors electronically. Here is the paper describing the study and development done.

The tiny, battery-powered wearable contraption can detect when you inhale, and uses its electrodes to stimulate the nasal septum (the little piece of cartilage in the nose that separates the nostrils). The Chicago team's device does not involve any actual chemical stimulation. The wearer isn't actually smelling external odors—he's simply tickling one of the nerve groups associated with smell in a way that makes him think he's sensing odors.

The smells? (Also) a mental issue

Most people know that we perceive smell using our olfactory bulb, but smell is actually a multimodal sensation. We have two systems that contribute to our perception. The olfactory bulb and nerve endings in our nose. They perceive intense odors such as vinegar, or the refreshing mint.

Jas Brooks, University of Chicago

The wearable Bluetooth nose stimulates this area to produce olfactory sensations, which the brain then fuses together with data from the olfactory bulb to complete the picture. I think it is the first convincing work in the direction of olfactory control. And it also has interesting features: for example that of being able to smell odors in both "stereo" and "mono" mode. This means that you can smell one odor with one nostril, and another odor with the other. Be careful, though: "stereo" smells are not exactly like those we experience in everyday life: there are surprises there too.

We are only at the beginning

Having exhausted the list of advantages of this experiment, it must be said that this "magnetic ring" on the nose is not yet capable of simulating very complex odors. And maybe he never will be, at least not alone. It may be possible to simulate a wider range of odors, Brooks says, but not just through trigeminal nerve stimulation. It is obviously the olfactory bulb that has the widest range of sensations. The trigeminal nerve is more like the tongue, which can only detect five tastes: sweet, sour, salty, bitter and umami. (Much of the subtlety of what we call taste is actually smell.) In other words, ok for vinegar, but we can't simulate smells like rain-wet grass.

What if we also stimulate the olfactory bulb? I do not know. For now, forget it. We should stick a long nasal swab in our noses. One in the presence of which a tampon for Covid would be like a handkerchief. We could perhaps do it with an internal implant, but the speech is premature.

There is also the challenge of replicating smells programmatically. “We don't know what the parameters would be to actually encode a smell digitally or electrically so that it can be decoded correctly later,” Brooks says. Not a small problem.

The usefulness of an odor simulator

What applications could this device find? The first that comes to mind is that of immersive reality. It doesn't matter how good the graphics are, or how accurate the touch technology is. Walking in a virtual forest and smelling pine would be the real leap in quality.

But it wouldn't be just a game. “We already have phenomenal olfactory experiences, perhaps to which we don't pay too much attention,” says the researcher. “A device like this could lead to a purely olfactory augmented reality, which truly transforms the way we interact with everyday smells.” It's not clear to me how, but that's okay.

With imagination you can visualize everything, anyway. Also a world of olfactory notifications. Who wouldn't want to smell a nice scent of flowers when a beautiful girl calls us? Or smell something burning and understand that they are calling us to sell us something... Jokes aside: having a nose ring like this could make us perceive odors that we otherwise don't perceive. Dangerous odors, such as carbon monoxide. It would be very useful, for example, to rescuers of earthquake victims.

To return to slightly more playful experiences, being able to relax with a “playlist of smells” would be wonderful, right? Imagined itineraries, with a voice that invites us to a guided meditation, and smells that take us along a journey. “Walk in the vineyards”, with the smells of the must, or “a morning at the seaside”, with the smells of the sea breeze and who knows what else.