When it comes to renewables, the superstars are always solar and wind power: unsurprisingly, given the success of both sectors. Solar and wind power, however, have their drawbacks. They are not yet continuous, reliable and universally practicable. Energy storage and transport are crucial: progress has been made on both fronts, but batteries remain expensive to produce, maintain and replace.

What if there was an almost unlimited supply of energy in the world? And if it were "enough" to develop technologies that use this energy source? If that were enough, in one word: drilling?

The answer is to drill

The answer to these questions is and always has been directly under our feet: the core of our planet is hotter than the sun (even if it's cooling a little). All it takes is to drill deep enough to release some of its heat.

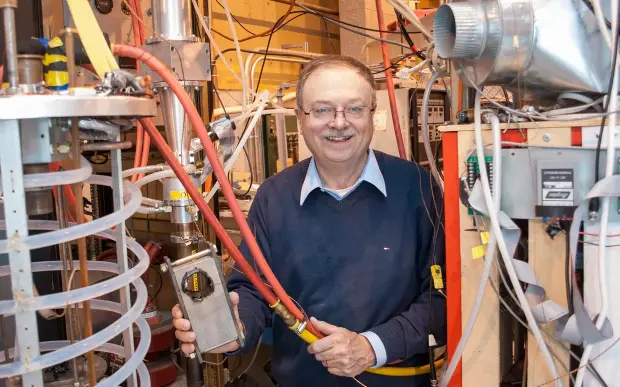

At least that's the intention he has Quaise Energy: the startup born within MIT in 2018 has recently obtained $ 40 million in new funding. But to really drill deep, you first need new drills.

The idea

To vaporize the rock instead of breaking it, it is necessary to replace the traditional tips with millimeter wave light beams. These “contactless” drills can penetrate up to 20km (12 miles) into the Earth's crust, where the rock reaches temperatures above 350°C (700 degrees Fahrenheit). Water would be drawn into the hole and converted to steam, then to energy.

“We have an access problem right now,” he says Carlos Aráque, co-founder and CEO of Quaise. “When we can drill 10 to 20 kilometers deep we will have access to a virtually infinite source of energy.”

It sounds promising, but the startup has yet to prove its experimental technology works. By the way, does it work? Let's take a small step back first.

Geothermal energy explained to my dog

Geothermal energy does not receive much attention because it depends on special conditions. Iceland, for example, has made its own electricity grid almost 100% renewable using geothermal and hydroelectric energy: it is a leader in Europe. However, Iceland is a rare case: a beautiful island made up of volcanoes and glaciers, and when fire and water meet near the surface, you don't even need to drill.

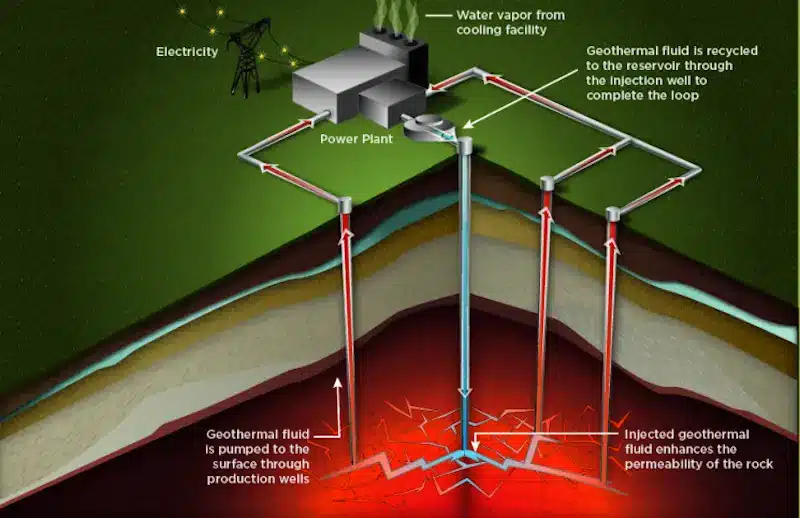

Conventional geothermal plants use steam rising through cracks and crevices in the rock to heat structures and drive turbines that produce electricity. Not at all easy and not at all obvious.

The new generation geothermal energy

This is why geothermal energy is once again aiming to create the right conditions, rather than looking for them elsewhere. Advanced geothermal systems (EGS) penetrate hotter rocks with fewer natural cracks and cracks. They then fracture the rock using high-pressure fluids (a technology borrowed from the oil and gas industry known as “fracking”). I said fracking and already turn up my nose.

Of course, EGS supporters point out that the fluids used for EGS are safer and pose a lower risk of groundwater pollution. Ditto for the risks of inducing seismic activity, because EGS systems would produce smaller fractures in the rock, using lower pressure than fracking which recovers shale oil and gas. My doubts remain, however.

The Quaise system is even further ahead

The type of geothermal system that Quaise proposes, the company says, is light years away even from the newly-developed geothermal system.

Drilling at very high depths means hitting the rock at higher temperatures. So high as to produce "supercritical" water. A fourth state beyond the solid, liquid and gaseous state, during which water contains 4 to 10 times more energy per unit of mass, doubling its conversion into electricity.

In summary: you would get more energy, and you would get more electricity from that energy. Most importantly, it could be done anywhere in the world.

Drilling down there is a feat

The more you drill, the hotter the rock becomes: an advantage that comes at a price. With conventional technologies there is a point beyond which drilling is no longer possible. Simply put, the electronics melt, and the drill bits are literally ripped off. To replace one at those depths, it might take a week to lift it up, two hours to replace it, and another week to bring it back down again.

The solution (not so original or new) is contactless drilling.

Paul Woskov from MIT, whose research underlies Quaise's approach, took 10 years just to demonstrate the physics involved in this technology. The system for drilling without touching rock includes a beam of millimeter-wave energy, an electromagnetic frequency in the microwave territory generated by a gyrotron on the surface. The microwave beam is “fired” into the drill hole together with a gas (nitrogen, air or argon) and vaporizes rock layers deep in the Earth. Then the gas binds to the vaporized rock and brings it to the surface as a cloud of volcanic ash.

The first tests, the result of the grants received, will start in 2024.

Quaise will begin drilling with this method in just under two years, gradually increasing the depth. The only bottleneck is this technique, the company claims: everything else is ready, including the power plants.

Indeed, current power plants could be "adapted" by drilling nearby and replacing fossil fuels with geothermal energy, with an ecological footprint from 100 to 1000 times lower.

To put it this way, this would sound like the true ecological transition. A great vision. Sure, still early, but it deserves a lot of attention.

The Earth's 'geological engine' still has it for at least a billion years. It is an energy source available from anywhere on the globe.