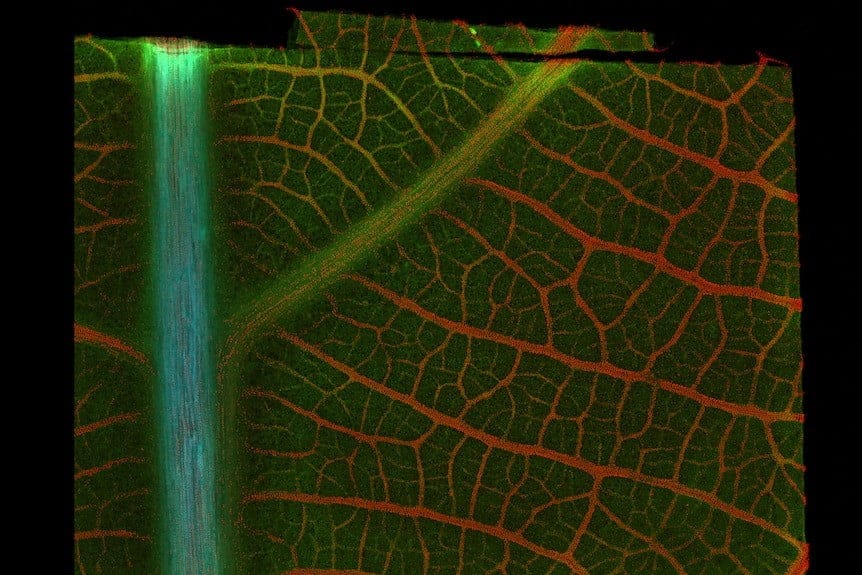

When the scientist Alan Baker analyzed the appearance of a plant discovered in the Philippine jungle, the sap it exuded had a jade green glow.

The shrub was a recently discovered species, the phyllanthus Balgooyi, a rare amount of vegetation that naturally absorbs significant amounts of metal components from the soil.

The fluorescent sap turned out to be made up of as much as 9% nickel.

The hyperaccumulators

An undoubtedly welcome discovery. Not a shock, however: as Professor Baker's analysis of so-called "hyperaccumulators" had already discovered plant species that appear to absorb everything from cobalt to zinc, even gold.

“These are vegetation that can pick up components from the soil in much larger quantities than normal vegetation,” says Professor Baker.

Of the 300.000 plant species recognized on Earth, only about 700 have hyperaccumulation properties.

Plants that exude metal

The blue latex of the rare pycnandra acuminata present in New Caledonia contains 25% nickel.

Scientists are trying to find out whether or not cultivating this vegetation can be an environmental substitute for mining. Is there industrial potential for agromining? Can metal be “cultivated” instead of mined?

College of Queensland plant specialist Dr. Antony van der Ent also recognizes this practice with the term “fitomining”.

Macadamias, baby

In his chemical evaluation laboratory on the outskirts of Brisbane he is currently carrying out evaluations on what is now the best-known hyperaccumulator of all: the tree of Macadamia.

It is widespread in Southeast Asia, New Caledonia, Cuba and Brazil.

Macadamia wood has a great ability to absorb manganese: its leaves and sap are rich in it.

The cuttings of this woody vegetation can be dried and its ash is a real "bio-mineral".

It is an extraordinarily high quality mineral, which can therefore be processed using normal hydrometallurgical strategies

Antony van der Ent, College of Queensland

Metallic farms

Nickel is a highly sought-after component in the modern era: it is vital in the production of lithium-ion batteries and chromium steel.

A “metal farm” that seeks to extract it from plants has long been active in Malaysia, developed by researchers at the College of Lorraine.

If you think it is a purely experimental project, consider that every year it collects between 200 and 300 kilos of nickel. Per hectare.

Nonetheless, time is still needed to create a new supply chain for agromining

We hope this can contribute to part of the nickel collection, with a more environmentally sustainable approach. “Metal farms” have a future precisely for this reason.

And also another possible field of application: that of the reclamation of former mining sites.

Other potential medical applications? Transforming metallic wood into biomass for food supplements (especially for zinc and selenium) or for "biofortifiers" capable of enriching other crops.

In other words, agromining can be a unique alternative to agriculture.

The soil in massive components of theAustralia Central, for example, is rich in selenium, and the vegetation that grows there has proven to be an extraordinarily environmentally friendly hyperaccumulator.