The risk of dying from a virus doubles approximately every nine years of life. And it's a pattern that's almost identical to a host of other diseases. But why are older people vulnerable to so many different things?

One of the major hallmarks of the aging process in many mammals is inflammation. Not the local response we associate with an injury, but a kind of “inflammatory background noise,” which gets louder the longer we live. This condition contributes to the development of atherosclerosis (fat buildup in the arteries), diabetes, hypertension, frailty, cancer, and brain and cognitive decline.

The discovery on brain aging

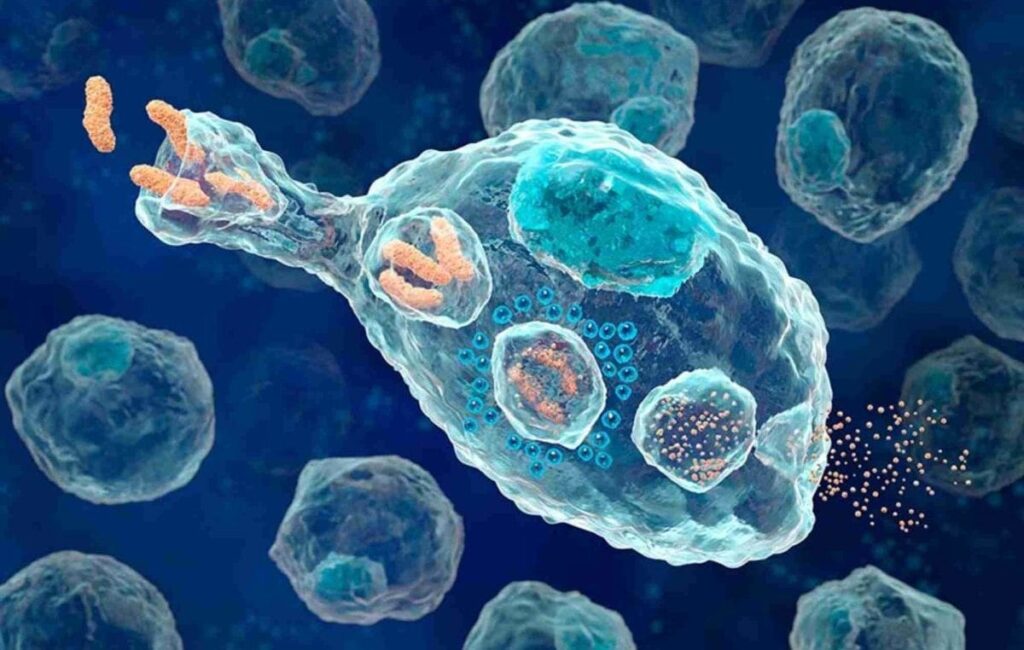

A new study published in Nature has just revealed that microglia (a type of white blood cell found in the brain) is extremely vulnerable to changes in the levels of prostaglandin E2 (also known as PGE2), a major inflammatory molecule.

The team found that exposure to this molecule affects the ability of microglia and related cells to generate energy and carry out normal cellular processes.

Fortunately, the researchers found that these effects occurred only due to the interaction of PGE2 with a specific receptor on microglia. By stopping it, they were able to normalize cellular energy production and reduce brain inflammation.

The result was brain improvement in older mice.

Huge prospects

The extraordinary discovery offers hope that the cognitive impairment associated withaging is a transitory state that we can correct, and not the inevitable consequence of brain aging.

PGE2 levels increase as mammals age for several reasons. One of these is probably the growing number of cells in different tissues that enter a state called cellular senescence. This means they become dysfunctional and can cause tissue damage by releasing PGE2 and other inflammatory molecules.

The role of macrophages in brain aging

The researchers also found that macrophages (another type of white blood cell linked to microglia) of people over the age of 65 produce far more PGE2 than those of young people.

It is not a small thing, indeed: exposing these white blood cells to PGE2 suppresses the entire pattern of energy generation and cellular behavior.

The authors of this study managed to "turn off" a receptor responsible for the interaction between macrophages and PGE2. They treated white blood cells, grown in the laboratory, with drugs that activate or deactivate this receptor. It worked great, at least in a Petri dish.

What would happen in an intact body?

The researchers conducted a second phase of testing on mice. They took genetically modified animals in which the EP2 receptor had been removed and observed the brain aging process. They then tested their learning and memory by observing their ability to walk through a maze, and perform other memory tests.

Genetically modified older mice learned and remembered as well as young ones. These effects could be duplicated in normal elderly mice giving them one of the drugs that deactivate the EP2 receptor.

It may represent a new approach to the treatment of late age cognitive disorders.

Meanwhile eat fruit!

There is still some way to go before we can start using these drugs in humans, even though the prostaglandin systems are very similar.

But this study shows that reversing brain decline is possible. And it sheds light on a fascinating series of observations that link diet and cognition.

It has been known for some years that eating blueberries and other fruits and vegetables such as strawberries and spinach improves brain activity in rodents and elderly people.

They are foods rich in molecules such as resveratrol, fisetin and quercetin, which kill or block senescent cells.