On January 9, the World Health Organization notified the public of a viral outbreak in China. Several cases of pneumonia had been reported in Wuhan, probably after exposure to live animal vendors at the local seafood market.

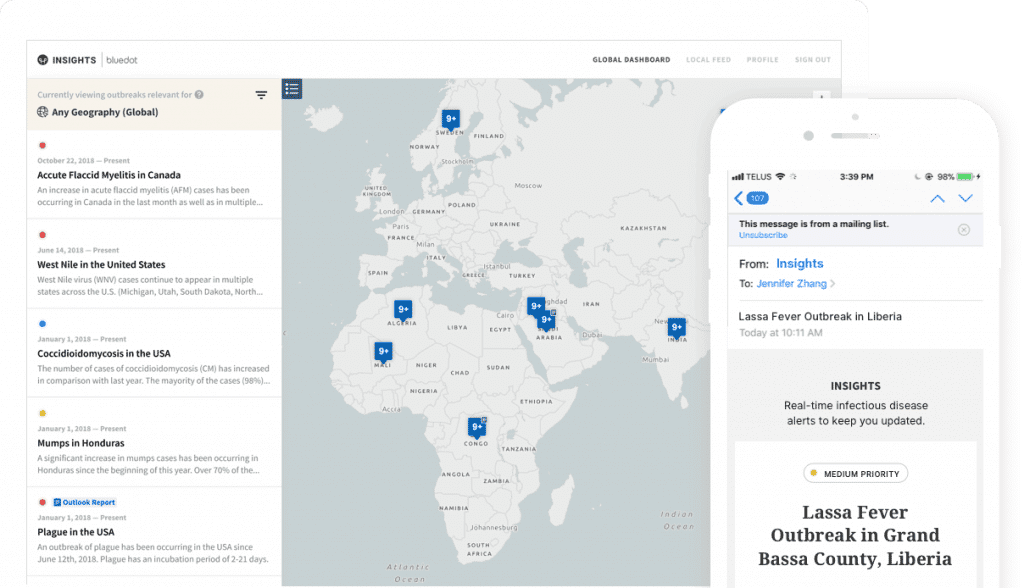

The CDC (US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) had released the news of the Coronavirus a few days earlier, on January 6th. BlueDot, a Canadian health monitoring platform, beat them both by sending news of the outbreak to its users on December 31st.

How is it possible?

BlueDot uses an AI-based algorithm. BlueDot's AI analyzes foreign language news, information networks on animal and plant diseases and official bulletins. And on December 31 it warned its customers in advance to avoid dangerous areas such as Wuhan.

Speed is crucial in preventing the spread of an epidemic, and Chinese officials have never performed well on disease, air pollution and natural disasters.

WHO and CDC rely on these same health officials for their disease monitoring. Not well.

Maybe an AI can get there faster. “We know that governments cannot be relied upon to provide information in a timely manner”, he claims Kamran Khan, founder and CEO of BlueDot. “We are able to gather news of possible outbreaks, small murmurs on forums and blogs, indications of unusual events taking place.”

Social media? Not very reliable

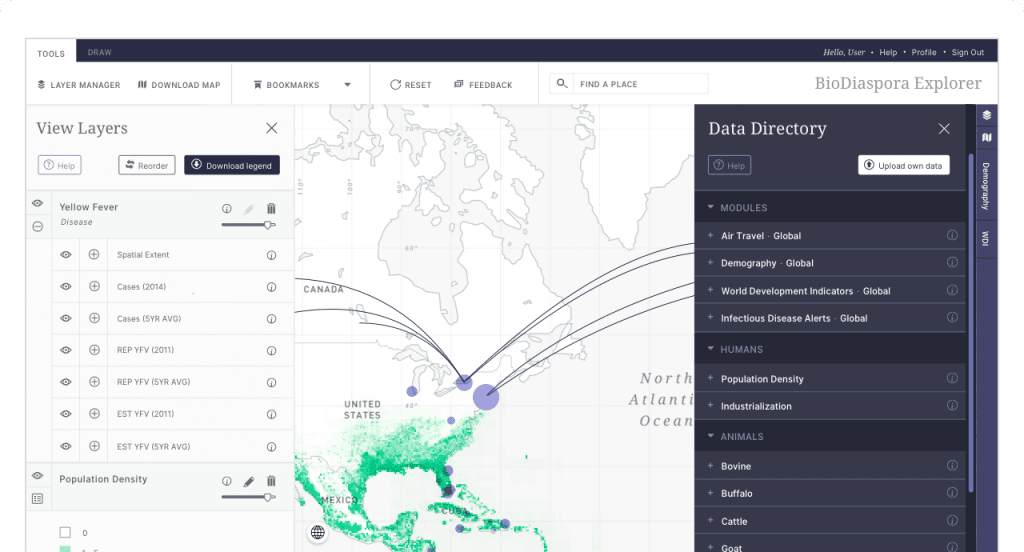

Khan says the algorithm doesn't use social media posts because the data is too messy. But it has an ace up its sleeve: access to ticketing data from global airlines that can help predict where and when infected residents will be headed next. BlueDot's AI correctly predicted that the virus would jump from Wuhan to Bangkok, Seoul, Taipei and Tokyo in the days after its initial emergence.

The BlueDot manager worked as a hospital infectious disease specialist in Toronto during the 2003 SARS epidemic. That virus started in provincial China and spread to Hong Kong and then Toronto, where it killed 44 people.

“There's a bit of deja vu right now,” says Khan about the coronavirus epidemic today. “In 2003 I saw the virus overwhelm the city and paralyze the hospital. There was a huge amount of mental and physical stress and I thought “Let's not do this again”. “

After testing several predictive programs, Khan launched BlueDot in 2014 and raised $ 9,4 million in venture capital funding.

The company now has 40 employees: doctors and programmers who develop the disease monitoring program. A “cyber monster” that uses natural language processing and machine learning techniques to sift through news stories in 65 languages, along with airline data and reports of veterinary disease outbreaks.

Coronavirus, it still serves the human factor

Once AI completes automatic data monitoring, human analysis takes the lead. Epidemiologists check that the conclusions make scientific sense and compile a report that is sent to clients (government agencies, businesses and public health).

BlueDot reports are then sent to health officials from a dozen countries (including the United States and Canada), airlines and hospitals where infected patients could end up. BlueDot does not sell its data to the general public, (but is working on it).

- Synthetic but alive: cells that challenge the boundary between artificial and biologicalDNA as a building material for multifunctional synthetic cells, stable up to 50°C. Potential applications in regenerative medicine, drug delivery and diagnostics.

Google tried BlueDot before, but it failed

BlueDot isn't the first to seek a solution for public health officials, but it hopes to do better than Google. Its Google Flu Trend service, which analyzed and attempted to predict flu trends, was shut down after it “missed” its predictions about the severity of the 140 flu season by 2013%.

Perhaps the timing is premature? BlueDot won where Google failed. He successfully predicted not only SARS, but also the location of the Zika epidemic in South Florida (in a publication in the British medical journal The Lancet).

It remains to be seen if BlueDot will be successful again, in the Wuhan Coronavirus case.

“The outbreak is likely much larger than what public health officials have confirmed,” says James Lawler, an infectious disease specialist at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, who treated quarantined Ebola patients in 2017 and 2018.

He is not wrong: quarantine cities are now 18, and nearly 60 million people are in quarantine. While waiting for the completion of the two "instant" hospitals built in a few days by the authorities, the healthcare facilities in the epicenter of Wuhan are in enormous difficulty.

Lawler and others say the coronavirus outbreak will continue to spread. We do not yet know how many people will get sick and how many of these will die before the epidemic abates.