DNA, our "code of life", hides secrets that can save lives: today, perhaps, there is one less. A group of scientists has made a truly interesting discovery: engineered bacteria capable of detecting tumor DNA in living organisms.

Bacteria and DNA: a revolutionary dance

Technology is making possible what was once considered impossible. The joint efforts of scientists fromUniversity of California, San Diego and Australian researchers have created bacteria capable of “seeing” and detecting tumor DNA within living organisms. In six words? Bacteria that can detect cancer.

Even in the past, bacteria have been modified for various diagnostic and therapeutic roles (even against cancer), but lacked the ability to identify specific DNA sequences and mutations outside of cells. This is where it comes in”Cellular Assay for Targeted CRISPR-discriminated Hhorizontal gene transfer,” or as scientists like to call it, CATCH. More than an acronym, the promise of a future in which early diagnosis could be the rule, not the exception.

“Sensor” bacteria of tumor DNA: the discovery

The leader of the scientific team, Jeff Hasty, a professor affiliated with several departments at UC San Diego, shared his thoughts. “When we started this journey four years ago, the idea of using bacteria as mammalian DNA sensors was a puzzle.” But like any great puzzle, once solved, it opens the doors to infinite possibilities.

How exactly does it work? Well, it's all about the behavior of tumors. The latter release their DNA into the surrounding environment. Although current technology allows purified DNA to be analyzed in the laboratory, the ability to detect tumor DNA in the same environments into which it is released was lacking. The CATCH methodology uses CRISPR technology to examine “free” DNA sequences at the genomic level, comparing these samples to known cancer-causing sequences.

A future full of hope

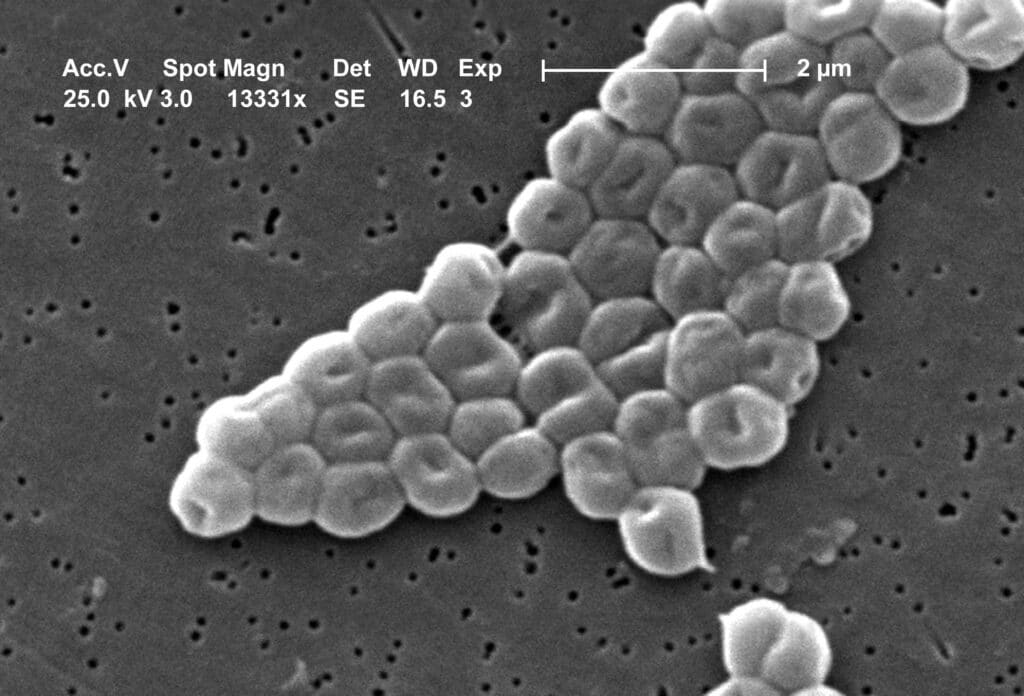

With the collaboration of Susan Woods e Josephine Wright from Australia, the bacterium Acinetobacter baylyi it was made into a sensor and “specifically tuned to the DNA” of the KRAS gene, which often mutates in many tumors. The innovation is based on the concept of “horizontal gene transfer,” in which organisms exchange genetic material in a way that deviates from the usual parent-offspring genetic inheritance.

Siddhartha Mukherjee, an associate professor at Columbia University, expressed excitement about the ramifications of this discovery. “The future will see diseases fought by cells, not just pills,” he says. The potential of a live bacterium capable of detecting tumor DNA within the intestine offers a great opportunity to preventively identify and eliminate gastrointestinal tumors, and more.

The work undertaken (and published in Science, I link it here) involves further refinement and development, Hasty and his team at UC San Diego are intent on perfecting this biosensor. And with passion, determination and science on their side, they could change the history of medicine.