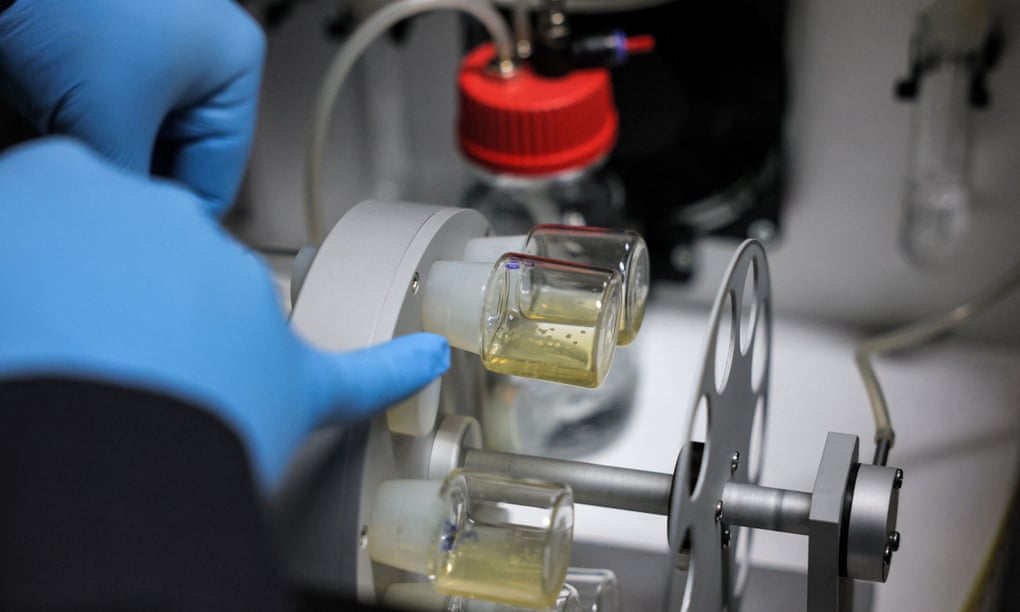

In a Cambridge laboratory, a group of scientists is giving birth to a new form of life: synthetic human embryos. I'm not talking about robot babies or androids, but embryos created with stem cells, completely avoiding the need for eggs or sperm.

Although similar to those found in the early stages of human development, these synthetic structures do not have a beating heart or the rudiments of a brain. However, they include the cells that would typically give rise to the placenta, the yolk sac and the embryo itself.

Epic creation

It's the teacher Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, the University of Cambridge and the California Institute of Technology, to drive this bold exploration of the mysterious “black hole” of the embryonic development period. This is because, at the moment, scientists can only grow embryos in the laboratory up to a legal limit of 14 days.

Even these synthetic embryos, obviously, will not have the possibility of going beyond laboratory test tubes. But they offer a valuable opportunity to study how the beginning of human life works and, potentially, discover which processes can go awry, leading to genetic disorders or miscarriages.

Synthetic embryos, race for knowledge

The world of science is in a frantic race to decipher the mysteries related to the very first part of our lives. Professor Żernicka-Goetz's team and a competitor team at the Weizmann Institute in Israel they had already demonstrated that stem cells from mice could be encouraged to form embryo-like structures, complete with intestinal tract, rudiments of brain and beating heart.

This new wave of research has left the law struggling to keep up. At the moment, these entities lab-grown crops fall outside current legislation in the UK and most other countries, raising huge ethical and legal questions.

Concerns about the future

It is unclear whether these synthetic embryos could, in theory, develop into a living being. In the past, synthetic embryos derived from mouse cells appeared almost identical to natural embryos, but when they were implanted into the uterus of female mice, they did not develop into live animals.

There remains a huge question mark as to whether the obstacle to more advanced development is purely technical or has a more fundamental biological cause. And this only increases the urgency for stronger legislation, a new bioethical challenge.

The current scientific race does not seem to have any intention of slowing down: the world must be ready to keep pace with new developments, and avoid dangerous drifts.