It would seem that even viruses cannot escape the law of the strongest that reigns in nature.

A recent study has shown that some microscopic organisms have the ability to actively feed on viruses, and perhaps there are many more of these types.

Ma what exactly are they viruses? These are tiny particles composed of genetic material capable of replicating within the cells of other organisms, taking control of them and becoming parasites. This has led to a long debate on their nature (are they "living" beings or not?): they certainly have a crucial role in the life of every other creature, including us human beings. And now we know that they also have predators that are greedy for them.

The discovery of “virus eaters”

Building on previous research on chloroviruses, viruses common in aquatic environments that infect green algae, scientists at the University of Nebraska wanted to find out whether some microscopic beings could harness viruses as an energy source.

To test this hypothesis, they collected water samples from a pond and introduced a wide variety of microscopic organisms. Then, they added large amounts of chlorovirus to the water and waited a day to see if there were any significant changes.

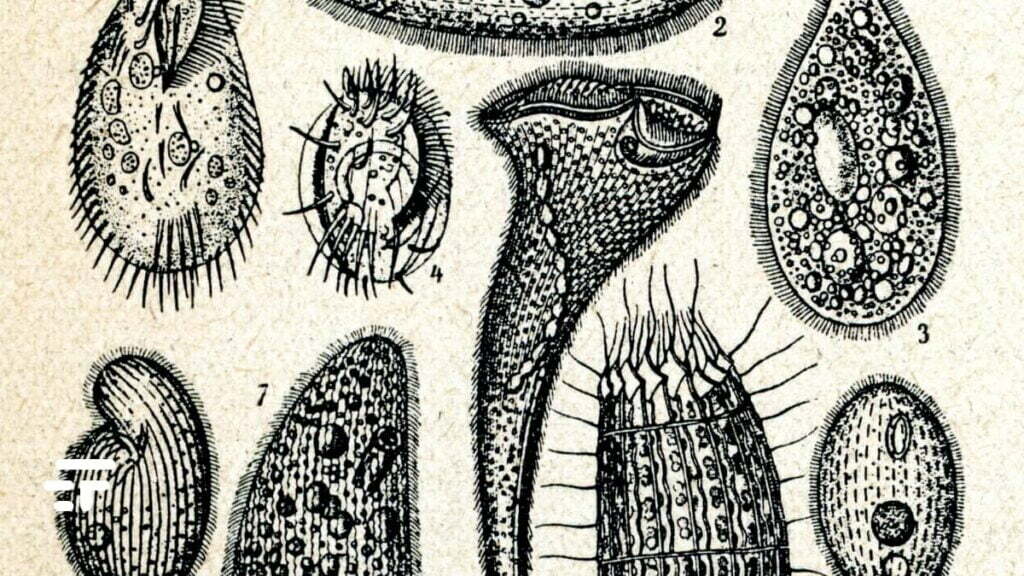

The result? The discovery of an incredible species of single-celled protozoan called Halteria, capable of exploiting viruses as a source of nourishment. Indeed, as their only diet and reason for living: these microbes are unable to grow if they do not eat chlorovirus.

The study, recently published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (I link it here), is the first to demonstrate that some microbes can only survive by feeding on viruses.

Gourmet microbes

The main author John DeLong, associate professor of biological sciences, compliments. “Viruses are composed of highly nutritious substances: nucleic acids, nitrogen, phosphorus. It was highly probable that some organism would sooner or later appreciate these extraordinary resources.”

If Halteria and other microbes work as we think, it will have to totally change our view of the global carbon cycle.

DeLong and his team say they have also identified other "vivovorous" microorganisms: they now aim to establish to what extent the phenomenon occurs in nature, or if it is influenced by the laboratory environment.