The first person to receive a pig heart transplant died this week, two months later the operation. The death of Mr. David Bennett it occurred at the University of Maryland Medical Center, where he had been treated for pneumonia, and it suddenly worsened.

Bennett's son praised the hospital for giving his father this last chance, however, saying the family hopes this effort will help find a solution to the organ shortage in the future.

“We are grateful for every moment, every dream and every sleepless night that led to this incredible feat,” said David Bennett, Jr.

Pig heart and other organs

For decades, doctors have tried to transplant animal organs into humans to save lives. Bennett, a handyman from Hagerstown, Maryland, was the right candidate for this new venture simply because otherwise he would have been sentenced to death: Even after the January 7 operation, he knew there was no guarantee it would work.

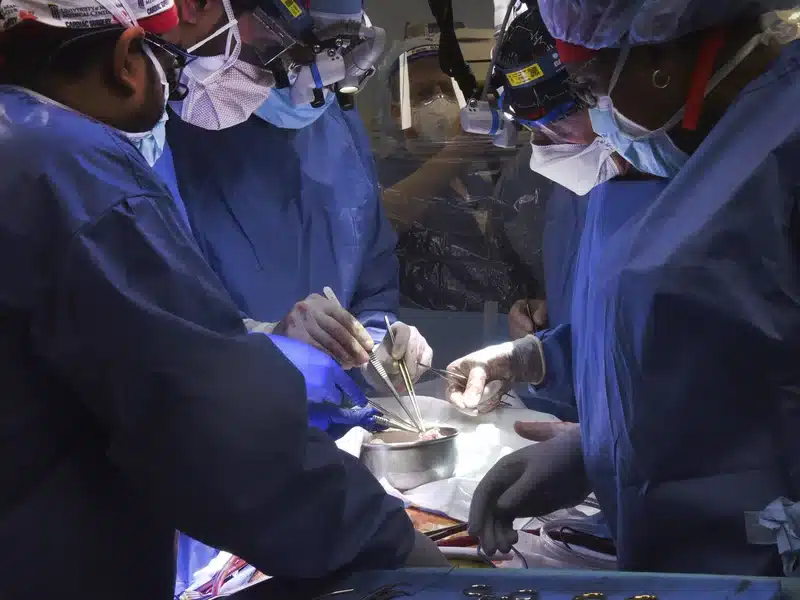

“We are devastated by the loss of Mr. Bennett. He was a brave and noble patient who fought to the end,” said Dr Bartley Griffith, the surgeon who operated on him.

Scientists modified the animal to combat organ rejection

The surgery requires the donor heart to be transplanted into a suitable recipient. Since previous xenotransplantation attempts had failed due to the recipient's body rapidly rejecting the foreign organ, Maryland doctors used a genetically modified pig heart. Specifically, to remove pig genes that cause hyperfast rejection.

The decor initially seemed good. Bennett's heart was still beating, and the institution had regularly informed the public about his recovery. Among the messages, also a video in which Bennet himself watched TV from his bed while he worked with his physiotherapist.

It was the most surviving xenograft ever, a new record. The previous one was established in 1984 when Baby Fae, an already seriously ill infant, was transplanted with a baboon's heart.

Organ transplants, another source is needed

Hundreds of thousands of people around the world die each year waiting for an organ. Many still die before being added to long waiting lists. Attempts, including through xenografts, as in the case of this pig heart, are needed.

Pigs have long been used in human medicine, including pig skin grafts and the implantation of pig heart valves. But transplanting whole organs is much more complex than using highly transformed tissue.

From Mr. Bennett's experience, researchers have gained invaluable information about how the genetically modified pig heart works. The next question is whether this lesson is enough to convince authorities to approve a clinical trial.