Senegalese farmers are about to build their own Great Wall, but theirs will have a breakthrough. It will be completely green.

Should you fly over the city of Boki Diawe, in northeastern Senegal, the sight of freshly sown seeds in carefully designed circular gardens that look like eyes planted in the Sahara Desert would surely catch your eye.

The gardens, known locally as Tolou keur, are the most recent incarnation of the project The Great Green Wall, which I told you about here. They were designed by Aly Ndiaye, a Senegalese agricultural engineer who could not leave Senegal when the borders were closed.

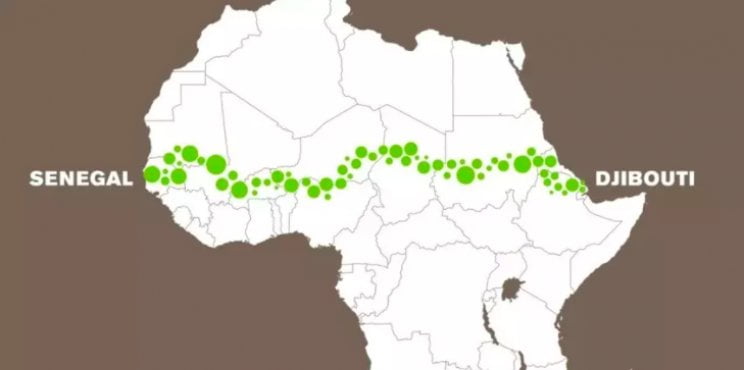

The initiative, launched in 2007 by the African Union with support from the European Union, the World Bank and the UN, was originally intended to prevent desertification by “stopping the Sahara” as it moved south. The plan was to plant a belt of trees 16 kilometers (10 miles) wide and 7000 kilometers (4.350 miles) long across the Sahel region, from Senegal to Djibouti.

Changes in progress

The program encountered a number of (not all unpredictable) problems. Among the major ones, the difficulty of planting trees in the arid savannah and the lack of funds. According to United Nations estimates cited by Reuters, the overall program only managed to plant 4% of the promised 100 million hectares of trees and complete it by 2030 as planned it could cost up to $ 43 billion.

Hence the idea of "shooting" the Sahara in localized points. The circular garden represents a new approach to the Green Wall project.

Circular mini forests to stop the Sahara

In the circular gardens being sown there are plants and trees resistant to hot and dry climates, such as papaya and mango. One of the curvilinear internal rows is even dedicated to medicinal plants. Three months after the completion of a garden in the Sahara, its agents begin a two-year series of monthly inspections to check its progress.

I hear you: You might be wondering why they are planted in a circular pattern. The reason is that circular beds allow roots to grow inward. This traps liquids and bacteria and improves water retention and composting. Cool, huh?

According to Senegal's reforestation agency, the “Tolou Keur” gardens, now around two dozen, have been doing well since the project began. When Senegal had to close its borders to the coronavirus, villages had to become more self-sufficient as many depended on foreign food and medicines. When they say that necessity sharpens the ingenuity, they say it right.