A team of researchers from Nanyang Technological University, Singapore has designed a device to communicate with plants. More or less. The tiny electrode can both detect and send electrical signals to a small carnivorous plant and elicit a response.

What do plants “know”?

Playing with plant electrical signals could open up many possibilities, the team argues: they could allow data to be monitored for information on plant health before problems develop. Signals could potentially also be sent to the plant to stimulate it.

A year ago researchers in Alabama observed the ability of plants to communicate with each other via electrical signals sent through the subsoil. I talked about it here.

“Climate change threatens food security around the world. By monitoring plants' electrical signals, we may be able to detect possible danger signs and anomalies." declares Chen Xiaodong, first author of the study.

Used for agricultural purposes, the system can let farmers know when a disease is occurring even before the effects appear on crops. Harnessing this knowledge could mean better and healthier harvests.

Of course it is important not to fall into the trap of thinking of plant communication as anthropomorphic, and therefore misunderstand it.

“A big mistake people make is talking as if plants 'know' what they're doing,” says the botany teacher Elizabeth Van Volkenburgh.

Biology teachers, researchers, and students all make the same mistake. I would much rather say that a plant senses and responds, rather than the plant 'knows'

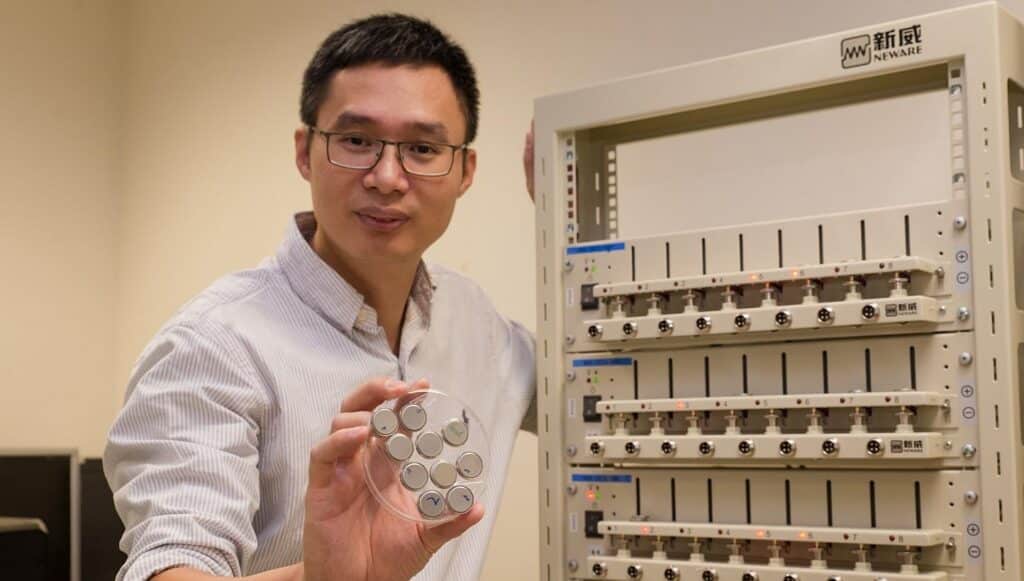

To detect these signals, the researchers developed a small, lightweight electrode, inspired by those used to perform echocardiograms. They glued it with hydrogel on the surface of the leaves of a small carnivorous plant, the Venus flytrap (Dionaea muscipola).

When the tiny electrode, just 3 millimeters in diameter, was attached to the Venus flytrap, it successfully recorded the plant's electrical signals.

Vegetable robots?

“Plant communication” is not a one-way street: as mentioned, we should also be able to to send pulses.

Using a smartphone, the researchers did just that, sending a pulse to the fly trap that caused it to close the leaves on command.

By connecting the plant to a robotic arm, the team created a hybrid robot capable of picking up a small thread using the leaves and their long, delicate extensions.

Plants are inherently modular, taking on a wide range of shapes, forms and capabilities, and “can be isolated and installed on a variety of platforms,” the team writes in their paper, published in Nature Electronics.

Integrated with current “flexible” electronics, such modularity could potentially be used to build plant-based robots, sensors and healthcare devices.