Zhang Tongjie, 52, is a Chinese researcher who could play a crucial role in a field that was previously unthinkable in the celestial empire: the search for extraterrestrial life.

Over the past six years, the academic has worked tirelessly to make China a major player in the search for extraterrestrial intelligence, or SETI. And now he believes he is on the eve of a triumph.

Scientists have been looking for evidence of extraterrestrial life for decades. While these efforts have so far proved unsuccessful, they have not deterred researchers. Because? Simple.

Because it is highly unlikely that we are alone in a universe that is home to more than 100 billion galaxies.

SETI research in China

In China, SETI research is just starting to gain popularity. Yet Zhang, a professor of cosmology at Beijing Normal University, is already convinced that his country will, if so, be the first to detect signals from other worlds.

“We'll probably find it before the others,” he says. “They (the West) have more experience, but our telescope can detect things that theirs cannot.”

A great eye on the sky

Zhang is right about SETI, China's ace in the hole the Aperture Spherical Radio Telescope (FAST) from five hundred meters. A giant observatory built on top of a mountain in the southwestern province of Guizhou in 2016. The facility is the largest single-dish radio telescope in the world. about 2,5 times more powerful than any previous tool of its kind.

Many see FAST as a game changer for SETI, as it may be able to pick up signals from space lost during previous observations.

Zhang has been lobbying Chinese authorities for more telescope access for years: in August, these efforts finally paid off

The National Astronomical Observatories have granted Zhang 17,5 hours of observations with the FAST (distributed) over several months. For weeks, he has worked extensively with his team to create a list of solar systems that he thinks are most likely to host intelligent beings.

Observations (China's first SETI project) started on Saturday.

Chinese SETI: the coming months

Over the next few months, the telescope will direct its giant antenna to dozens of galactic coordinates provided by Zhang, listening for any unusual radio activity.

The stakes are high: If Zhang makes a groundbreaking discovery, he hopes to get the official support he needs to grow China's SETI community. But if it fails, it may be even more difficult to observe the sky in the future.

Though the odds of making history are slim, Zhang insists his team has a better chance than any other before them.

“Maybe it's not powerful enough yet, but FAST is the best SETI tool we have in the world,” he says.

Accidental “alien” hunter

Born in a rural region of the eastern province of Shandong in 1968, for Zhang, stargazing was not a childhood passion.

His interest in science developed after the Cultural Revolution in the late 70s, when Chinese leaders launched a campaign to modernize the country. He initially hoped to become a mathematician, but having failed to win a place on a university mathematics programme, he fell back on physics.

In 1993, Zhang earned a bachelor's degree in cosmology, and has advanced his academic career over the past 20 years. The thought of spending time with SETI looking for extraterrestrials had barely crossed his mind.

“I was just as curious about aliens as normal people,” he says. “I never thought I'd do it alone.”

A research trip to the USA in 2014 changed everything.

Zhang spent several days at the University of California, Berkeley, a school known for its SETI research program since the late 70s. The university developed the SETI data collection instruments that are now installed on many of the world's leading radio telescopes, including FAST.

“When I was at Berkeley, I saw with my own eyes that they were developing real instruments and writing programs for SETI. It wasn't just a far-fetched idea. This convinced me,” Zhang recalls.

Dan Werthimer, chief scientist at the SETI research center in Berkeley, met Zhang during his trip. Remember that the Chinese professor got excited as he introduced his team's work, especially when the conversation turned to FAST, which was then under construction.

“We're interested in this question of 'are we alone?' For thousands of years,” says Werthimer. “So, there's this telescope that could answer the question. How can you resist? “

The couple have been working together ever since. Berkeley focuses on developing tools for SETI data collection, while Zhang works with FAST (which does not yet open to projects led by international researchers) and analyzes the collected data.

The first Chinese SETI astronomer in history

Zhang's love of SETI was a bold move, Werthimer says. Most modern SETI research is based on theories of radio astronomy, a field in which the Chinese professor had no experience. Yet he decided to jump regardless.

“Most people don't do that at their age,” Werthimer says. “I haven't changed fields in my career. It's a pretty bold and interesting thing to do. “

In fact, the decision was even braver than the American thinks. Before Zhang, no Chinese astronomers had attempted SETI research, and the field was often dismissed as pure science fiction.

SETI's reputation had been tarnished by association with wild theories of ufology, which took off in China after the country began opening up to the West in the late 70s. A group of UFO enthusiasts founded the China UFO Research Association in 1979 in the central Chinese city of Wuhan, recruiting thousands of members.

Two years later, the group began publishing a journal (The Journal of UFO Research) that later claimed to be “the most widely circulated SETI journal in Asia.”

Over the next few decades, the magazine was filled with speculation about the Bermuda Triangle, and letters from people describing encounters with alien spaceships.

Zhang distances himself from the publication. “Nothing is proven,” he says. “It's not science and I don't want to be associated with it.”

In China, SETI struggles to gain support and recognition

Even decision makers who see it as a serious science are often reluctant to provide funding: China is eager to establish a reputation as a world leader in science, but SETI research may not produce concrete results for years. Or maybe never.

At Beijing Normal University, Zhang continues to maintain his “day job” teaching and researching as a cosmologist.

SETI research is a secondary activity for now. Zhang receives no financial support and manages his projects from his home office together with two of his assistants. In these 17,5 hours that the authorities have given him at FAST he dreams of making discoveries that will convince officials to support his work in the future.

For the past two years, Zhang's team has had to content itself with conducting observations collecting SETI data while the telescope observed other targets. Zhang could not point the antenna at the areas of his choice.

Zhang is not alone, however

The lack of support for SETI is not unique to China. In the US, Congress has repeatedly cut funding for NASA's SETI project, with the senator Richard Bryan who, during a speech in the 90s, labeled the program a hunt for “little green friends.”

Berkeley is one of the few American institutions that still focuses on SETI, relying on private funding from an initiative called Breakthrough Listen underwritten by the Russian-Israeli billionaire Yuri Milner.

It's hard to get funding for things that don't pay off in a few years. In astronomy, of course, people think on a very long time scale, but most people don't.

We don't even know what to look for

There is uncertainty in the SETI community about the most effective way to search for alien civilizations. The dominant method until now has been to search for “unnatural” radio signals (of the latest, sensational, I have spoken here). Messages intentionally transmitted to Earth from a distant civilization, or radio waves accidentally spilled into space, such as chatter from cell phones and televisions.

But this approach is based on a bold assumption: that other civilizations are more or less like ours.

“It's hard to predict what another civilization is doing,” Werthimer says. “We try the kinds of things we would do, but that might be completely the wrong approach.”

But Chinese researchers are using the same methods

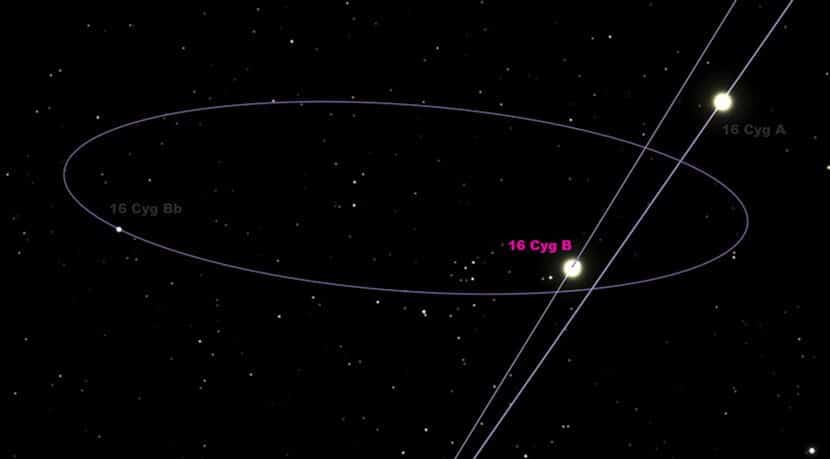

China's SETI (Professor Zhang and his two students) has already identified around 70 solar systems within the Milky Way galaxy for observation by FAST. They all have a stable sun and planets with the right conditions to hold liquid water – the best ingredients for life to emerge.

“I think there's a good chance we'll discover something we don't know from the targets we've chosen,” he says Zhao Haichen, a second-year student at Beijing Normal University who joined the project last year. “But it's hard to say what we can find.”

Zhao, who like Zhang is from Shandong province, first became interested in SETI after reading “The problem of the three bodies“, a Hugo Award-winning novel by the science fiction writer liu cixin on the fallout from Earth contact with an alien race.

Like the novelist, Zhao expects extraterrestrial civilizations to be probably far more advanced than ours.

Also Tao Zhenzhao, the other student who collaborates with Zhang, approached SETI after great science fiction binges. In his opinion, looking for a cosmic neighbor is simply a sensible thing to do.

“Our sun has a limited lifespan. One day, humans will have to leave Earth,” says the 26-year-old. “If we find extraterrestrials, it means we can migrate to other planets.”

What will be in the coming months for Chinese SETI?

Zhang has little time for science fiction sagas, dismissing them as "non-science".

He is focusing exclusively on growing China's SETI community. In October, the International Academy of Astronautics named Zhang to the SETI program committee, despite his relatively short time in the field. He hopes this recognition will help him secure a grant from China's National Science Foundation.

The money would be vital to fuel future research, as well as attracting Chinese aspiring scientists to the field, Zhang says.

Much will depend on the data that will arrive from FAST in the coming weeks. Though he dreams of a breakthrough, Zhang knows there are never guarantees in SETI research.

“What we can find depends on our luck,” Zhang says. “Honestly, the most likely outcome is that we find nothing. It's like buying lottery tickets: most of the time you don't win."

Sometimes, however, Zhang imagines what would happen if the team detects an extraterrestrial signal.

The first step, he says, would be to create a large organization of astronomers from around the world to study the source of the signal. So, perhaps the team could train all the radio telescopes on the planet on that tiny speck in the universe, he suggests.

“If I find that there are actual signals, then wow,” Zhang says. “Not only all the SETI scientists, but all the astronomers will come running.”