The fight against HIV has marked another promising chapter. As trials of the VIR-1388 HIV vaccine begin in the US and South Africa, we are one step closer to a world where HIV could become a manageable or even eliminated threat.

The vaccine was developed over nearly two decades with the support of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, a National Institutes of Health American. And it could represent the final turning point.

VIR-1388: Not just a vaccine

HIV has represented one of the greatest medical challenges of our time. Since it was first identified in the 80s, scientists around the world have worked tirelessly to find a way to combat it. And now, it looks like we're getting closer to a potential solution.

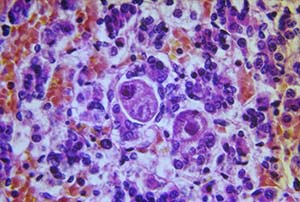

VIR-1388 is not a traditional vaccine. It is designed to instruct the immune system to produce cells T which can recognize HIV and signal an immune response to prevent the virus from establishing a chronic infection. But how exactly does the HIV vaccine work? It uses a cytomegalovirus (CMV) vector, which is essentially a weakened version of CMV. This vector delivers HIV vaccine material to the immune system without causing disease in study participants.

The story behind the CMV carrier

Cytomegalovirus is a virus that has coexisted with humans for centuries. Most people living with CMV experience no symptoms and often don't even know they have it. What makes CMV particularly interesting as a vector for an HIV vaccine is its ability to remain in the body for life.

This suggests it may have the potential to deliver HIV vaccine material and then help the body store it for a long time, potentially overcoming the waning immunity seen with more ephemeral vaccine vectors.

HIV vaccine: what awaits us?

The HIV vaccine trial will take place at six sites in the United States and four in South Africa, with a total of 95 participants. These participants will be randomly assigned to one of four study groups. Three of these groups will receive different doses of the vaccine, while the fourth will receive a placebo. Initial results are expected by the end of 2024, but the research won't stop there. An optional sub-study will continue to follow volunteers for up to three years after their first vaccine dose.

Perhaps, one day, HIV will be just a distant memory in the history books.