The fight against cerebral aneurysms, those fearsome swellings in the blood vessels of our brain ready to burst at any moment, is about to experience a completely revolutionary chapter.

A group of scientists from the RIKEN Center for Brain Science (CBS) in Japan has identified a series of genetic mutations responsible for the formation of these aneurysms. But that is not all. This discovery is accompanied by a second, perhaps even more exciting: the first pharmaceutical treatment capable of blocking the "wrong" signal transmitted by these mutations. The results are moving for me (I have a dear aunt affected by an event of this type). And exciting for everyone.

Findings that were published in the journal Science Translational Medicine on June 14. I'll link them here.

Aneurysms, cursed enemies

About 5% of the world's population lives, often without knowing it, with unruptured brain aneurysms. These structures, similar to overinflated balloons, often go unnoticed until they rupture, causing life-threatening brain hemorrhages.

Currently the only therapeutic option available is surgery, which however (as you will imagine) brings with it a series of non-negligible risks. Especially if the aneurysm is in a delicate location in the brain. That's why research is moving fast to find other, non-surgical options.

The two faces of cerebral aneurysms

There are actually two types of brain aneurysms: those intracranial fusiform pins (IFA) and those intracranial saccular (ISA), which represent approximately 90% of cases. Although mutations have been identified in arteries affected by IFA, the origin of ISA, which is much more common, remains shrouded in mystery.

To solve the problem, the RIKEN team analyzed the DNA of 65 aneurysmal and 24 normal arteries, finding that six genes were common between the two types of cerebral aneurysms IFAs and ISAs and NEVERs present in non-aneurysmal arteries. However, 10 other genes were exclusive to one of the two types of aneurysms.

Hirofumi Nakatomi, head of the project, said that “the unexpected discovery that more than 90% of aneurysms have mutations in a common set of 16 genes indicates that somatic mutation could almost always be the main cause.”

The discovery of the first pharmaceutical cure

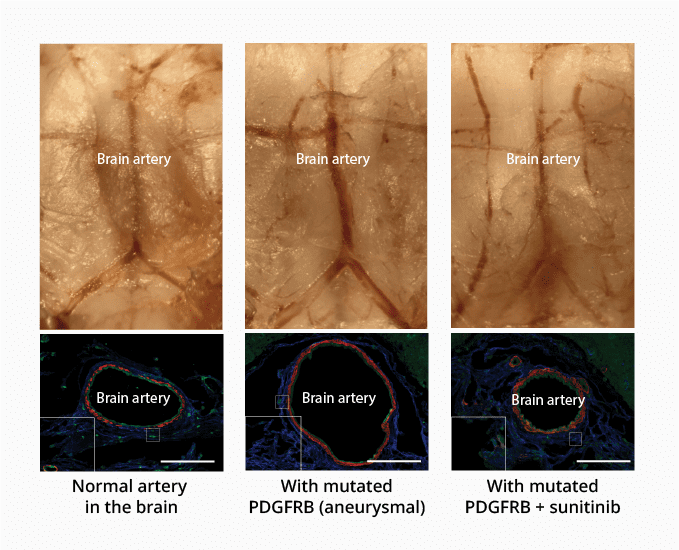

Subsequent tests showed that mutations of the six common genes activate the same biological signaling pathway. A path known as NF-κB. Later, the researchers discovered that a drug called sunitinib is able to block the effects of mutations in one of these genes, the PDGDRB, responsible for accelerating cell migration and inflammation.

The final stage of the research saw the establishment of an animal model to study brain aneurysms. Mice injected with a mutated variant of PDGFRB via an adenovirus developed brain aneurysms, with an artery at the base of the brain doubling in size in a month and becoming very weak. Sunitinib, administered to mice, blocked the effect of the mutated gene, keeping the arteries of normal size and strength.

Next steps

Now the goal is to demonstrate the effectiveness of this treatment also in humans, but an important obstacle will still remain diagnoses: Unruptured aneurysms are usually detected by magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomography during medical check-ups.

In the absence of these investigations, aneurysms remain invisible until they burst. While waiting to be able to identify them earlier and earlier, a new pharmaceutical treatment could represent an additional weapon in the fight against this silent threat.