Researchers at the University of California San Diego recently built a machine learning system that predicts what birds are about to sing.

If you don't find great practical possibilities, I'll start by telling you that real-time predictive speech synthesis for voice prostheses would already be a great thing. But the implications of understanding birdsong could go much further.

Song of the birds, an extremely articulated world

Bird singing is a complex form of communication that involves rhythm, tone and, most importantly, learned behaviors.

According to researchers, teaching an artificial intelligence to understand (and be able to construct enough to anticipate) birdsong is a valuable step on the road to replacing biological human vocalizations.

Motor prosthetics used primates as an animal model. There is no similar model for vocal prostheses. This is perhaps why these are more limited in terms of neural interface technology, brain coverage and behavioral study design.

It is not easy to “think” birdsong, but it is an important step

Songbirds are an interesting model of complex learned vocal behavior. Birdsong shares a number of unique similarities with human speech. Studying it has already provided excellent general information on the mechanisms and circuits underlying the learning, execution and maintenance of vocal motor skill.

But translating vocalizations in real time isn't an easy challenge. Current systems are still slow compared to our natural thought-speech patterns.

Think about it, because it's beautiful: cutting-edge natural language processing systems still struggle to keep up with human thinking.

We are still too fast for a car

When we interact with our Google Assistant or Alexa, there is often a longer pause than we would expect when talking to a real person. That's because the AI is processing our speech, determining the meaning of each word in relation to its capabilities, and then figuring out which reactions or programs to access to respond.

Of course, it is already amazing that these cloud-based systems work at this speed. But they are not yet good enough to create a real-time interface that allows the voiceless to speak at the speed of thought.

Research on birdsong

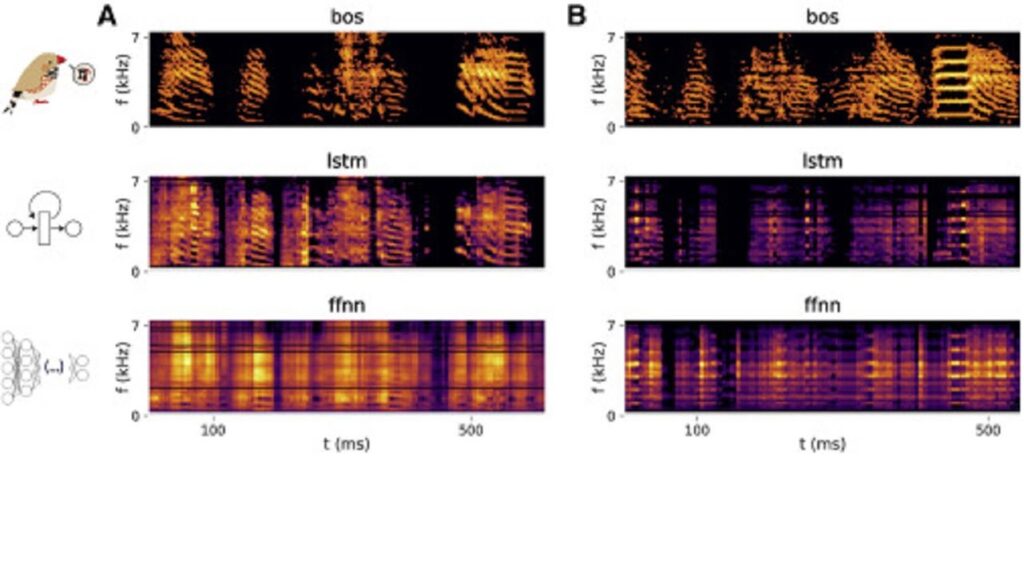

First, the team implanted electrodes into a dozen brains of birds (zebra finches) and then began recording brain activity during the birds singing.

But it's not enough to train an AI to recognize the neural activity of birds during their singing: even a bird's brain is too complex to fully map how communications work between its neurons.

So the researchers trained another system to reduce the songs in real time into recognizable patterns that the AI can work with.

It is very interesting, because it provides a solution to an outstanding problem.

The processing of birdsong in real time is impressive and replicating these results with human language would be historic.

But this first job is not ready yet. And it is not yet adaptable to other speech systems. It may not work beyond birdsong.

But if it did, it would be among the first, gigantic technological leaps for brain computer interfaces since the deep learning resurgence in 2014.