For some time we have been working on prosthetic limbs to make them increasingly suitable for the body. MIT researchers are taking a different approach, also working on the body: a new type of amputation can facilitate the use of prosthetics.

Most arm and leg movements involve two muscles, one of which lengthens while the other contracts. They call them “agonist-antagonist pairs”. Biceps and triceps are a good example: When a person bends their elbow, the biceps muscle contracts while the triceps muscle lengthens. This movement transmits sensory feedback to the brain, helping it track the position of the arm. What happens when there is an amputation?

In most conventional limb amputation techniques, the joined ends of the paired muscles are cut off. This is preventing them from communicating properly with each other. As a result, the muscle signals that are sent to the brain are confused. And for many who get an amputation they have to watch what theirs is doing prosthesis, in order to guide its movement.

The new amputation procedure

In the new procedure, called agonist-antagonist myoneural interface (AMI), the severed ends of the paired muscles are joined again after the amputation itself has occurred. This reconnects their communication system, allowing the brain to better assess where the missing section of limbs would be in three-dimensional space if it were still attached.

After an initial mouse test dated 2017, MIT recently submitted 25 patients at AMI surgery at Harvard University-affiliated Brigham and Women's Hospital. MIT scientists they rated 15 of those people, each of which underwent a single amputation below the knee.

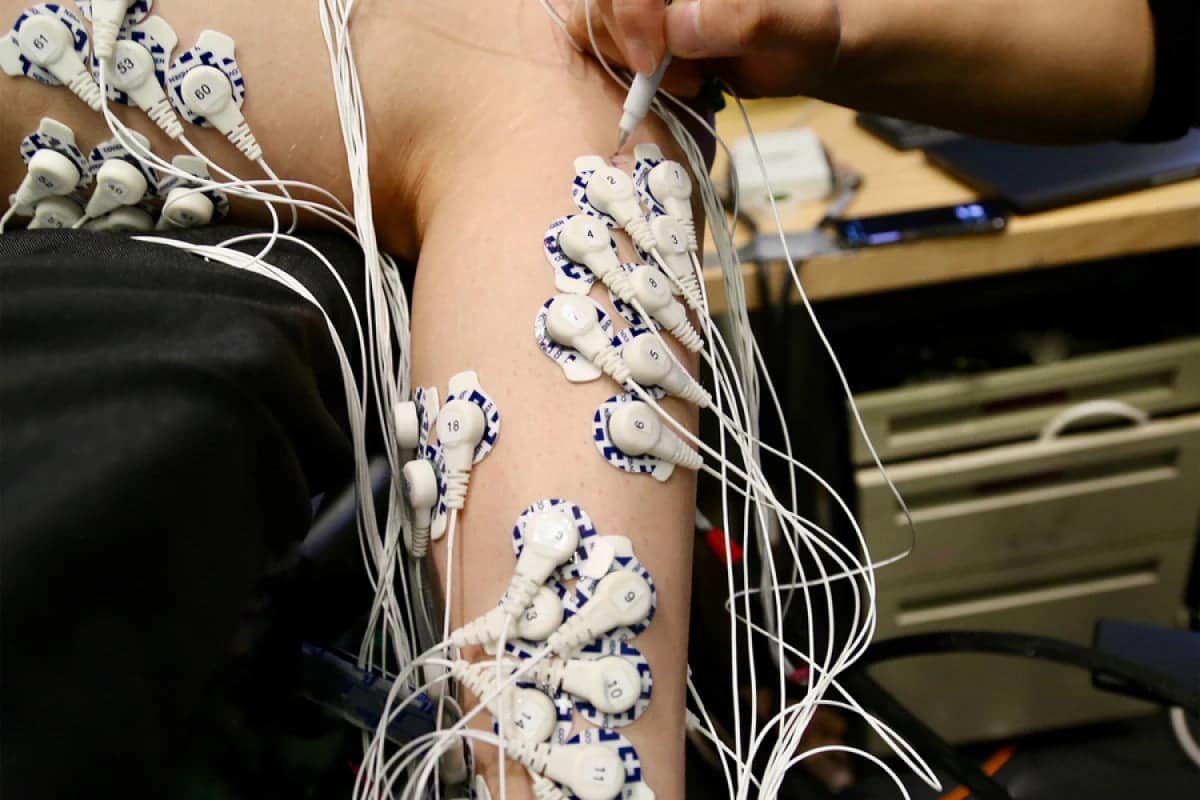

The test

consisted of having patients lie down with both legs raised, without a prosthesis in place. They were then asked to flex both their intact ankle joint and that of their "phantom limb" to varying degrees, while electrodes on both legs monitored the electrical activity of the muscles. Compared to a control group that had received a conventional amputation, amputees were found to have IMA they had much finer control over their phantom ankle – this was highlighted by the fact that the electrical signals in the stump of the amputated leg were significantly more similar to those in their intact leg, on which the ankle was actually moving. Likewise, brain scans showed that they were receiving more sensory feedback from the residual muscles. And as a side benefit, the AMI group reported much less residual limb pain.

Further studies will be necessary. Especially to see if the benefits of the procedure actually translate into better control over a real attached prosthesis. Scientists have developed a version of the surgery known as “regenerative AMI.” In this version, the grafted muscle segments can be used to reconnect agonist-antagonist muscles severed in traditional amputation.