Robots could take blood samples in the near future, benefiting both patients and healthcare professionals.

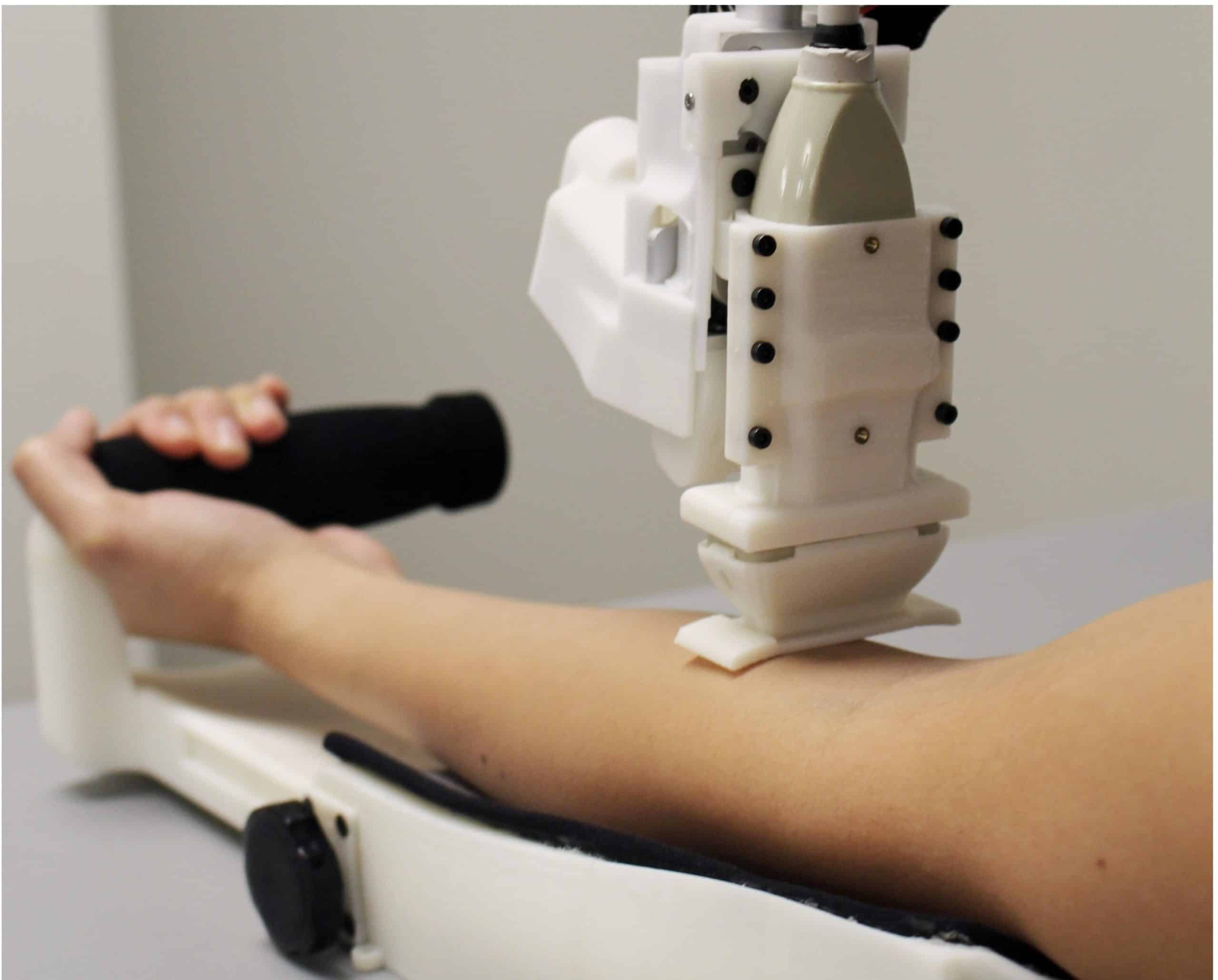

A team at Rutgers has created a blood-drawing robot that is as efficient as, if not more than, human operators. This is clearly indicated by the results of the first human clinical study of an automatic blood sampling and analysis device.

The device provides quick results and would allow healthcare professionals to relieve themselves. To spend more time treating patients in hospitals and other contexts, and not in manual and distracting operations.

The results, published in the journal Technology, are comparable to or superior to clinical standards, with an overall success rate of 87% for the 31 participants whose blood was drawn. For the 25 people whose veins were most easily accessible, the success rate was 97%.

The device includes an ultrasound robot that creates a real "map" of the veins: the machine that manages the samples and a centrifuge blood analyzer complete the system. The system could be used in bedsides and in ambulances, emergency rooms, clinics, doctors' offices, hospitals, wherever there are patients who require it.

The most widespread practice in the world

La venipuncture, which involves inserting a needle into a vein to take a blood sample or perform intravenous therapy, is the most common clinical procedure in the world, performed almost all the time by those heroes of the ward who go by the name of nurses. In Italy it is performed almost 200 million times every year, but according to previous studies doctors fail in 27% of patients without visible veins, in 40% of patients without palpable veins and in 60% of emaciated patients.

This is to say one thing that is obvious but still sounds bad: venipuncture is a major cause of patient injury. Additionally, difficult access to veins can increase procedure times by up to an hour, require more staff and result in increased costs.

“A device like ours could help doctors draw blood quickly, safely and reliably. There robotics and AI can prevent unnecessary complications and pain in patients caused by multiple needle insertion attempts”. This was stated by the lead author, a doctoral student in the biomedical engineering department of the School of Engineering at Rutgers University.

The next steps include refining the device to improve blood draw success rates in patients with difficult-to-access veins.

Comments are closed.