Jellyfish are the most efficient swimmers in the ocean, although quite slow. Researchers at Stanford University made a jellyfish swim three times faster by attaching it to a motor and creating a biohybrid robot with the jellyfish as a "scaffold".

Cyborg jellyfish are 10 to 1.000 times more energy efficient than other robots that swim, according to the document published in Science Advances.

The two researchers behind the study, the Stanford graduate student Nicole Wu and the professor John Dabiri, they hope their robot can be used for ocean monitoring or for taking underwater samples.

Cyborg jellyfish, how it was obtained

The researchers took four-leaf clover jellyfish (aurelia aurita, or “Moon Jellyfish”) the size of a dinner plate from the Cabrillo Marine Aquarium in San Pedro, California, and transferred them to a large artificial saltwater tank.

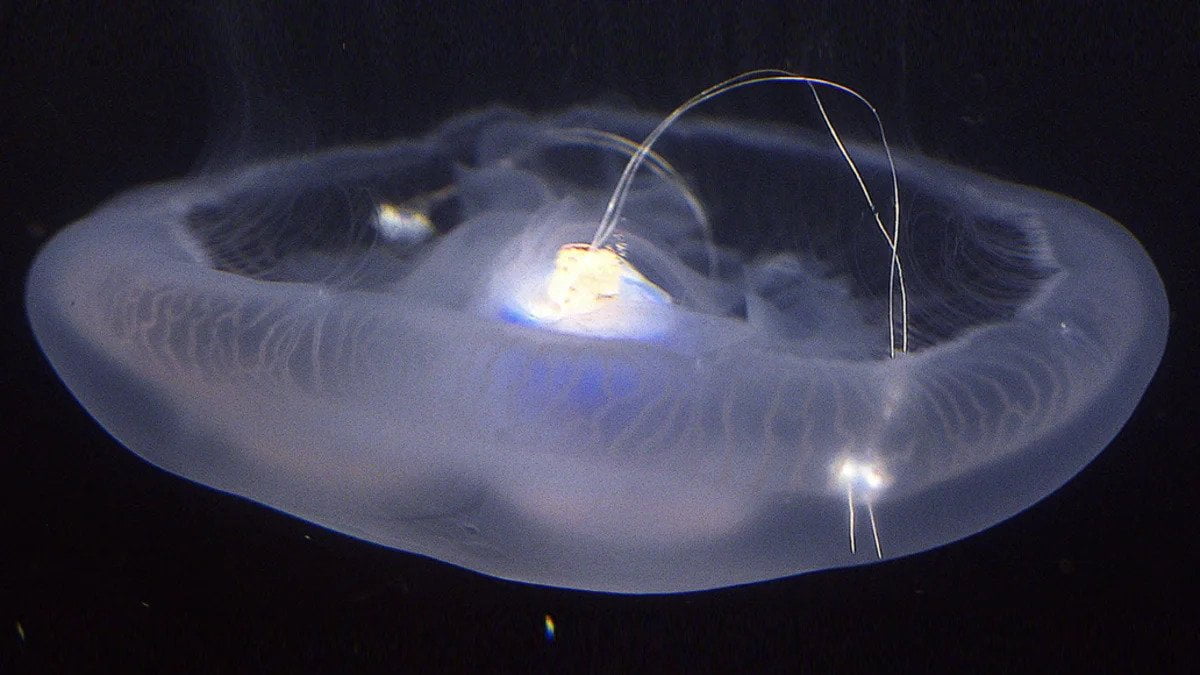

They designed a waterproofed and powered controller with a lithium polymer battery, a microprocessor and a set of electrodes, which were incorporated into the muscle tissue of the jellyfish.

Kind of like a pacemaker for a heart, but in this case, what looks like a bottle cap full of electronics prods the jellyfish to make them move faster. The cyborg jellyfish receives electrical discharges directly into the muscles, accelerating the pace.

Researchers, anticipating ethical objections to this work, they observed than jellyfish “They are invertebrate animals without a central nervous system or pain receptor. However, we have taken steps to ensure that no unnecessary tissue damage occurred during the experiments.”

Three experimental tests followed:

- The first to watch jellyfish swim alone without a controller connected;

- The second with the controller turned off to see how it affected the movement of the jellyfish;

- The third in which the controllers provided electrical stimulation.

Adding the controller without stimulation didn't seem to have much of an effect on the jellyfish. But for the smallest of the six test subjects, at pulse rates of 0,6 Hz (one pulse per 1,67 seconds), its velocity increased nearly threefold, from about 0,15 to about 0,45 diameters. bodies per second.

Why don't jellyfish swim so fast on their own?

The authors speculated that there is no evolutionary pressure for jellyfish to go so quickly, even if their body would allow it.

The authors write that they hope to improve the energy efficiency and controllability of the jellyfish robot and others biohybrid robots, including the insertion of signals to rotate the jellyfish and thus “remote control” it.