You might expect this to be somewhere in Asia, but the largest vertical insect farm is located in central Europe, in Dole, France. The production site is called Ÿnsect, is 17 meters high and is home to three trillion mealworms (Tenebrio Molitor). The CEO and co-founder of the company, Antoine Hubert, says that they are treated well, as long as they live: the trays where they are kept are kept at an optimal humidity of 60% and a temperature of 25-27°C. They remain like this, well nourished until their adult form, then killed with steam and transformed into oil, fertilizer, proteins.

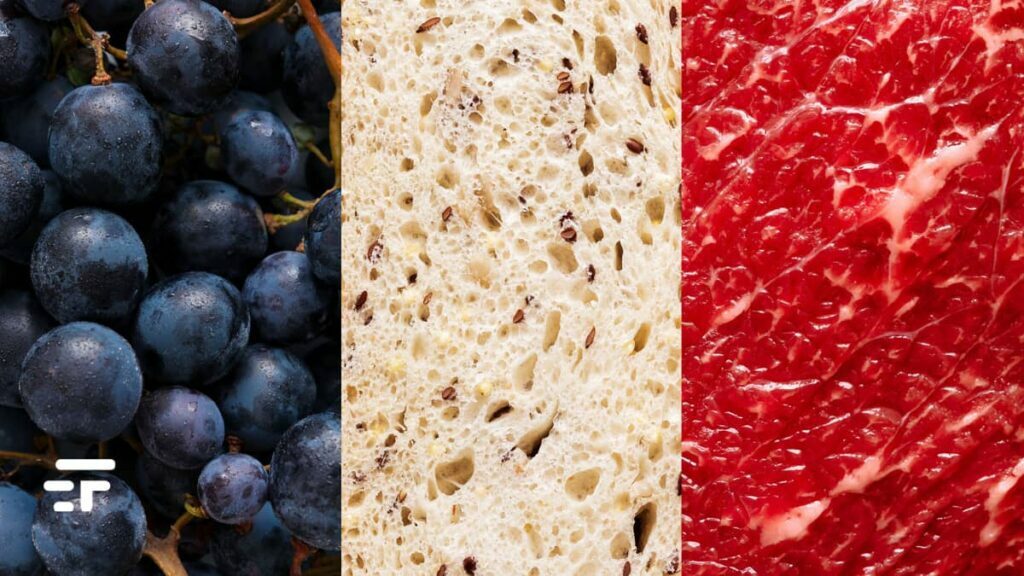

Protein: the magic word. The one that sparked an uproar in Europe over changes in eating habits. According to the new EU regulation approved and in force from January 24, cricket powder will now be allowed in food products for daily consumption, such as bread, crackers, biscuits. And many believe this is just the beginning. In this scenario, Ÿnsect aims to “get around” the obstacle. If you don't want a bug burger, we'll give bugs… to your burgers. The French company aims to grow insects for animal feed: insects to supply to fish, pigs and poultry, thus relieving pressure on the conventional use of agricultural land.

Insects of Europe

In recent years, insects have been the focus of scientists seeking alternative sources of protein to feed the growing global population. A nutritional comparison shows that edible insect species have higher protein potential than conventional meat products. To give you an idea, 100 grams of mealworm larvae contain 25 grams of protein, while 100 grams of beef contains 20 grams. Insects also have a higher feed conversion ratio than livestock: crickets require about one-sixth as much feed as cattle to produce the same amount of protein.

Despite these premises, all attempts by companies to commercialize insects as a main food source in Europe and North America have failed. At best, they have been labeled as a "fad", at worst, as an "attack" on local nutrition and even health. In any case, among the concerns there are also those of some researchers: according to the ecologist Åsa Berggren of the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences in Uppsala, “there are no rules on insects that can be imported”. Invasive species could be introduced which, if they escape from farms, would threaten local livelihoods and ecosystems. Why do we insist, then?

The food crisis is around the corner

With the world's population projected to grow to nearly 10 billion by 2050, the United Nations has sounded the alarm that food production will also have to increase by 70%. What are the plans at the moment?

THEvertical farming is becoming more and more popular thanks to advances in LED lighting, the cost of which fell by 94% between 2008 and 2015. More and more startups (also in Italian) are using this system to produce vegetables for human consumption. Estimates say that the global vertical farming market will grow from $3,7 billion in 2021 to $10,5 billion in 2026.

And the vegetable alternatives to meat? There the situation seems to be in total stagnation. Even if (for example) the stock exchange quotations of Beyond Meat have increased by 163% in three years, sales are stuck at 2020 levels. Same fate for similar companies and for the projects of the large fast food chains, which wanted to have their say in this sort of "vegetable transition".

In summary, it seems that the priority of reducing environmental impact has been overtaken by the passion for meat. For this reason she is convinced that her solution can work. And she's not the only one who thinks so.

France, the nation of insects?

Over the past ten years, Ÿnsect has grown significantly into a successful company. With an ability to produce more than 1.000 tons of insect products per year, using 98% less land and 50% fewer resources than conventional farming methods, the Ÿnsect site in Dole is the first and largest of its kind. However, it will soon be surpassed by the opening of a new site, also in France, in Amiens. By the end of the year, the company will also begin breeding mealworms in the US. CEO Hubert aims to open another 15 factories by 2030: by then, perhaps, the time will also be ripe for human consumption.

Competition in the field, meanwhile, is increasing. Another French company, the NextProtein, founded in Paris in 2015, wants to close the protein gap in animal feed by growing black soldier flies Hermetia Illucens. These flies were chosen for their fast-growing larvae and resistance to a variety of conditions, and are fed fruits and vegetables that would otherwise end up in landfill.

With these premises, France is a candidate as a leading nation in Europe for insect farming. It is no coincidence that two of the largest insect cultivation companies are French, in fact. There are obvious advantages for carrying out this type of activity: the INRAE, or the French National Research Institute for Agriculture, Food and the Environment, is the largest agricultural research institute in Europe. It has an annual budget of 1 billion euros ($1,1 billion) in 2021, and it also heavily funds these projects. There is only one “very small problem”: the tastes of the French.

Change mentality

I do it quick and easy: in France, only 2,2% of the population is vegan, vegetarian or pescatarian and there is a very strong meat lobby. This makes it difficult for activists to change public opinions on giving up meat. Benoit Granier, spokesperson for the French Climate Action Network in Paris, says it clearly: “the meat lobby is one of the biggest obstacles to the reduction of meat and dairy products in France”.

Granier points out that these groups spend millions on media campaigns to convince people to eat meat to be healthy. The farmers' union also supported meat, with a slogan that I would define as... impactful: "to save a farmer, eat a vegan". In 2020, the French consumed approx 84,4 kilograms of meat per capita spending almost 40 billion euros. 84 kilos of meat each. It is the country with the second largest livestock population in Europe, and it still imports large quantities of meat, otherwise it doesn't fit in. Perhaps this too is an excess, in its own way. As the EU's largest beef producer, France has a lot to do to reduce the environmental impact of agriculture.

And this (I say this to prevent the objections of both those "against" insects, like me who don't like them, and those "in favor") regardless of the "new foods". Insect farming, however, can only reduce emissions by feeding pigs, chickens and fish, but cannot help reduce emissions from raising cows that eat only grass and dried grain.

How will this story end?

The feeling is that the field of insect breeding (sooner or later we will talk about milling, at least in the case of the mealworm) will not stop. Companies like Ÿnsect are implementing a wide selection to choose the optimal "products" for consumption. This entire industry is carefully sharpening its weapons, both operational and media.

I say it all: I am not against human consumption of insects. They have always done it in the East. If anyone likes them, they can sit down: ditto if they are convinced by the media hype. I don't know if they'll ever succeed with me, but I doubt it. Unless they trick me, but that wouldn't be a good thing: in fact, it would definitely be worth fighting.

My doubts, to tell the truth, are precisely about the "French" model, the one which involves using insects as animal feed. Some experts are quite pessimistic about whether insect farming interpreted in this way actually reduces emissions. Ultimately, by providing animal feed to farmers, Ÿnsect's products encourage industrial livestock farming, albeit to a lesser extent. Yet, the "conquest" of the tables by insects starts right here, from the center of Europe. We'll see.

My unsolicited opinion is that we need to encourage plant-based diets, and drastically reduce meat consumption. We have to do it for our health e for the planet. Of course, insect farming is still a response to climate and biodiversity collapse, but it would have to happen on a very large scale and in a short time, and frankly I see it as difficult. Especially if everyone has the same revulsion that I have.