Researchers at Irving Medical Center Columbia University they developed an organ-on-a-chip system composed of human heart, liver, bone and skin tissues and immune cells: a mini multi-organ model of the human body.

Engineered tissues are the basis of disease models: However, the human body is composed of a variety of tissue types that communicate physiologically. As a result, scientists are trying to develop organ-on-a-chip systems that can mimic more organs in the human body, and provide further information on the course of diseases and the effect of drugs.

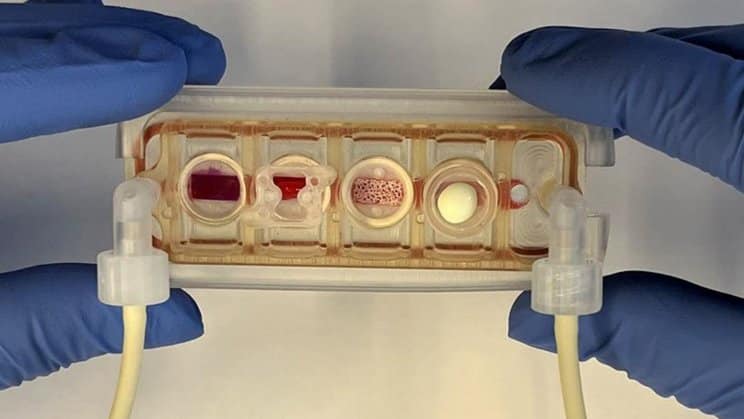

Multi-organ chip, the miniaturized human body

The multi-organ system on a chip is the size of a microscope slide. The various “mini organs” are derived from the same cell line as human induced pluripotent stem cells. And they are also “connected” to each other. As? From a “bloodstream” of immune cells.

What will it be for? To several things: among others, to study anticancer drugs. The first to be tested is the Doxorubicin, widely used and “suspected” of producing adverse effects.

The team developed a computational model to simulate the absorption, distribution, metabolism and secretion of this drug across “mini organs” on the multi-organ chip, and studied its effects.

The results

“We have identified some early molecular indicators of cardiotoxicity, the main side effect of the drug. The multiorgan chip was correct in predicting cardiotoxicity and cardiomyopathy. Factors that often require doctors to reduce doxorubicin dosages or even stop therapy,” says the project leader Gordana Vunj Vunjak-Novakovic.

Computational models can be used in future studies to accurately predict the effects of other drugs. More: to help interpret effects in clinical trials.

The team is currently studying variants of the multiorgan chip to study metastasis in breast and also prostate cancer, the effects of ischemia on other organs and more. Other studies will look at the impact of Covid on the heart, lungs and vascular system.