Most accounts of the 1918 Spanish flu say the pandemic officially ended in the summer of 1919, when a third wave of respiratory disease finally subsided, having killed at least 50 million people worldwide.

However, the virus continued to kill. A variant that appeared in 1920 was lethal enough to be considered a fourth wave. Deaths in some cities even surpassed those of the second wave, which was responsible for the vast majority of deaths. The "fourth wave" of the Spanish flu also hit hard the countries in which the population already had a high natural immunity from the virus, after two years of infections and despite the fact that the lethality had decreased.

The fourth wave

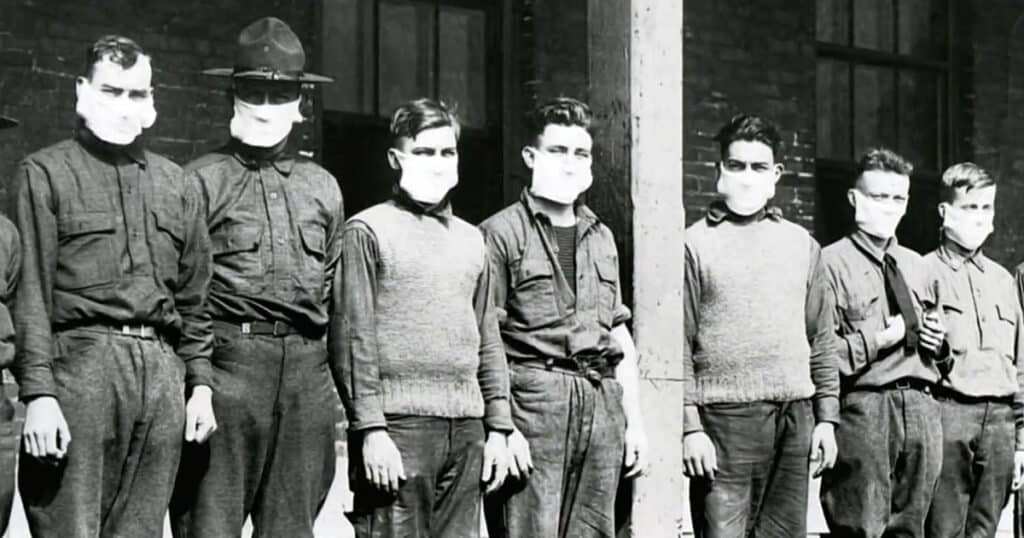

Nearly all Western cities also imposed restrictions during the Spanish flu pandemic, which peaked in the fall of 1918, and many controls were introduced the following year as well. In 1920, however, no city responded to the appeal. Governments and ordinary people were tired of the flu. The newspapers were full of scary news, but no one cared anymore.

People of the time ignored the fourth wave, and so did most historians. Deaths returned to pre-pandemic levels only in 1921 and the Spanish flu virus transformed into the normal seasonal flu, but the world had moved on months earlier. We shouldn't repeat that mistake.

Let's not ignore the lessons of the Spanish flu

It's true, never before do we have every reason to be optimistic. First, why Omicron cases are decreasing in much of the world. Second, in the most affected countries (including mine, Italy) almost the entire population has now recovered or vaccinated, and has a stronger "immune baggage" than in 2019. Third, although Omicron is extraordinarily adept at infecting the upper respiratory tract (which makes it more transmissible) seems less good at infecting the lungs than previous variants.

It is entirely possible and perhaps even probable that due to improved immune responses, the virus will continue to decline in lethality and, like the 1918 Spanish flu, may lose its ability to bind to lung cells altogether.

Yet, after two years of struggle, the dangers that come with it Omicron today they are overconfidence, indifference and tiredness.

It's time to hold on

Signs of tiredness (or excessive optimism) are practically everywhere. I will stay on the Italian case, but the example could easily be brought to all of Europe, or to the United States, or to the UK.

Although in Italy over 90% of the population over 12 is fully vaccinated, progress on the third dose is practically stagnant: to date a lower percentage, around 83%, has received the "booster" which helps protect against the most serious consequences of the virus. Although the Government has practically forced the opening of all schools, only 20% of children between the ages of 5 and 11 have received a complete education. (source updated 8/2/2021 – https://www.governo.it/it/cscovid19/report-vaccini/)

And above all, people (understandably tired) are loosening their grip on precautions, encouraged by the media and measures that are perhaps slightly premature in the current situation.

This is handing over control to the virus

The result could lead to a still high average of deaths, and for too long. People, most of them fragile, not numbers to be taken into account as inevitable "side effects".

The virus may not be over. While there is a good chance that future variants will be less dangerous, the only thing we can say with certainty is that if new variants become established, it will be because they develop the ability to evade our defenses. And this, regardless of their lethality, could still make them very harmful.

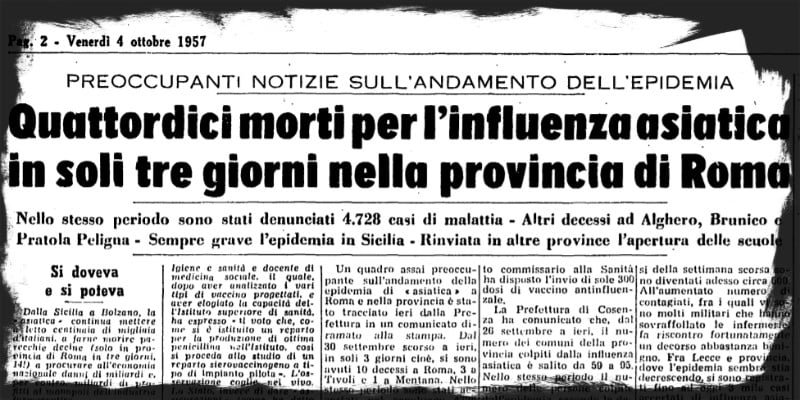

This was the case with the fourth wave of the Spanish flu, in 1920. But there is no need to focus only on the Spanish flu, and on the mistake of underestimating its "tails". This has been a mistake repeated again and again, with the flu pandemics of 1957, the 1968 and 2009. In the USA, 1960, a variant, which had yet to be completely eradicated, caused epidemic mortality that exceeded pandemic levels in 1957 and 1958. In 1968, a variant in Europe caused more deaths the second year, although, again, it was vaccination was available and many people had already been affected in the previous year.

Spanish flu and subsequent years, always the same mistake of "Lassez-faire" of politics and media

Also in 2009, variants emerged that caused serious diseases: a UK search revealed “a greater burden of severe disease among individuals over age 65” in the year following the epidemic, but “much less awareness in the media about influenza.” According to the study, the government's attitude was to blame. The public health response had been “very active” in providing information in the first year. In the second year, however, the strategy was "laissez-faire". As a result, the study concludes, "there were a large number of deaths and hospitalizations in intensive care, even among people without other illnesses and of working age."

These precedents should make us more cautious, and remain cautious even in the face of the "sirens" that promise us an unconditional surrender of the virus. We still need some time.

The Spanish flu teaches us that the war will end only under two conditions, and not immediately

Vaccines, the new antiviral drug paxlovid and other remedies will almost certainly end the pandemic, but only on two conditions: first, that billions of doses are widely available globally and that treatment with antivirals is possible even at home. Second and obvious, the virus does not develop resistance.

The end will not come tomorrow.

The immediate future is still in the hands of the virus, while we continue to fight with a better arsenal (vaccines, masks, room ventilation, antivirals and theunique monoclonal therapy which works against Omicron).

Media and politics may also have (legitimately) an interest in making us abandon the most stringent measures for (also legitimate) needs of economic recovery and social balance as a whole, without considering thousands more deaths as a simple statistical consequence.