Does a sound scare us? Our breathing quickens. Do we break a leg? We gasp in pain. When we are in pain or anxiety our breathing becomes faster, and the research had not yet found an answer to the phenomenon.

Now, a team of researchers from the Salk Institute has discovered a neural network in the brain that directly links breathing patterns to feelings of pain, anxiety and fear. The discovery could lead to an analgesic that prevents an opposite phenomenon: opiate-induced interrupted breathing that causes more than a few deaths from overdose.

A systematic review

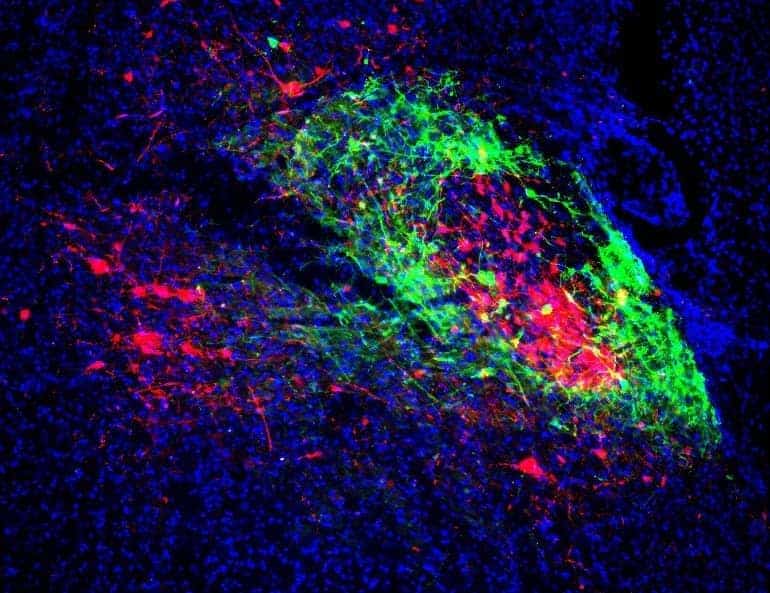

In work published December 17, 2021 on Neuron, the Salk Institute group looked at a group of neurons in the brain stem called parabrachial nucleus lateral, which is arranged in a core-shell configuration.

The researchers found that the shell neurons project to the amygdala, which is an area of the brain that processes fear and pain. Neurons in the shell also project to a region called pre-Bötzinger complex, which is responsible for generating the rhythm of breathing.

In summary: the core and shell influence each other based on inputs from these areas. It is the reason we were looking for, and it also scientifically explains the process by which realigning breathing (with targeted exercises and the contribution of meditation) has a positive impact on anxiety.

Coordinated breathing and anxiety or pain from the same area

“We are the first group to demonstrate how the lateral parabrachial nucleus coordinates both breathing, pain and anxiety,” says the paper's senior author, sung han, assistant professor at the Salk Institute.

By understanding the circuitry in this brain region, we may be able to separate breathing regulation and pain regulation to develop a drug that inhibits pain sensations without repressing breathing.

This is what happens with opiates. In previous work, Han's lab has shown that opiates such as morphine suppress breathing by activating specific receptors, called receptors μ-opioids (DEAD), which lead to the inhibition of the neurons that express them.

Reactivating MOR-expressing cells could reverse respiratory depression, and in those cases save from overdose death.

What are the next steps?

“We found very intricate circuits involving inputs upstream and downstream of these neurons. By uncovering this circuit mechanism, we can better explain why breathing can often be coordinated with pain and anxiety,” says the first author Shijia Liu, a student of Han.

Han is happy that the team's discovery has a translational application, meaning that it may be able to help people. “The problem with opioids is that they reduce the pain but also the person's breathing,” Han says. “So people can die from them.”

To prevent this from happening, we might find drugs which are beneficial against anxiety and pain, but without collateral damage.