The prevailing theory about the origin of our universe goes something like this: About 13,7 billion years ago a single particle exploded. We call it the Big Bang. This explosion created an ever-expanding universe that ultimately became home to the planet we call Earth.

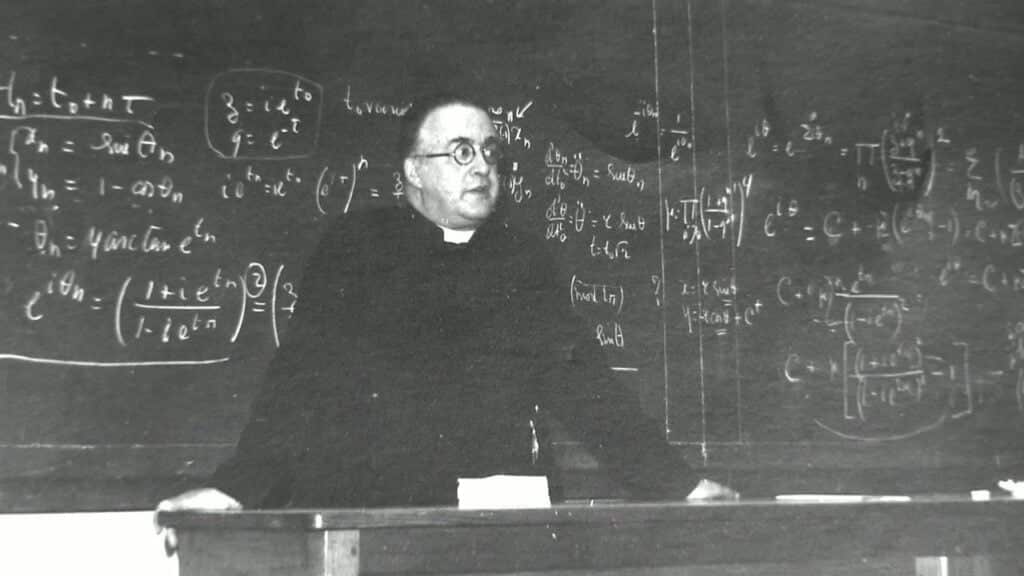

The theory, called the Big Bang, first appeared in a scientific article written by the physicist in 1931 Georges Lemaitre. Most of our current hypotheses about the universe and its rate of expansion are based on his ideas.

The first cracks in the Big Bang theory

In 2019 that rate of expansion, called “Hubble's law“, was questioned by various teams who determined that the expansion rate had been incorrectly calculated or that there was something seriously wrong with the universe (the first hypothesis more likely).

Scientists are still fixing things and working towards an explanation that can reconcile both the Big Bang and modern observations.

Why is it so difficult to understand how things went?

The reason we can't just put some numbers into a supercomputer and determine the truth is because, of course, we don't have all the information.

Trying to determine how old the universe is by measuring its current rate of expansion is like trying to choose the winner of an F1 grand prix based on a blurry photograph of the rear wheel of any racing car. With the lens open by chance.

To this end, the Big Bang theory really only works in one case: if we assume that this was the beginning of our universe. In this case (and I repeat, only in this case) it becomes the only piece of the entire puzzle that corresponds to what we are actually able to see and measure.

What if the Big Bang wasn't the beginning?

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, a physicist at the University of New Hampshire, has a different theory. He says it makes more sense to assume the universe has been expanding forever.

The universe may not have had an initial moment and we may be living in what is called an eternally expanding universe. One that was expanding exponentially even before what we call the big bang. Mathematically, this seems like the most likely scenario, assuming inflation is correct.

Chanda Prescod-Weinstein

The ramifications of such a theory may seem trivial: one explanation for a number is as good as any until we can measure more. But many of our hypotheses regarding both classical and quantum physics are based on the idea that time is more than a simple construct.

The importance of time

Whether we're talking about the Big Bang, or Newton's laws, or quantum physics, the idea is that there is a dimensional quality called time encoded by distinct points that represent the beginning and end of an event.

Without a finite moment at the creation of the universe where nothing became something, there is no point of origin for time. There are no beginnings.

The concept of infinite expansion without a birth, without a beginning can be difficult to metabolize, but that doesn't make it nonsense.

After all, it seems paradoxical to even imagine a time when the universe itself, and therefore time, did not exist at all. How long, then, would time not exist before it began to flow? On balance, even the explanation of the big bang has weaknesses.

And, paradox for paradox, if instead time has always existed (because the universe itself has always existed) then perhaps it never existed. What, in fact, is time without beginning or end?