In 1873, Dr. Joseph Howe injected goat's milk into the veins of a tuberculotic patient, immediately recording dizziness, back pain and uncontrollable eye movements. He doubled the dose: the patient died.

Despite the unfortunate result, the doctor did not give up, continuing his experiments on dogs (killing 7) and then three years later he was convinced: to replace human blood, human milk would be needed, not goat's milk! No. Not even. With yet another dead patient, the terrible conclusion: milk was not the ideal substitute for blood, it was not an ideal synthetic blood.

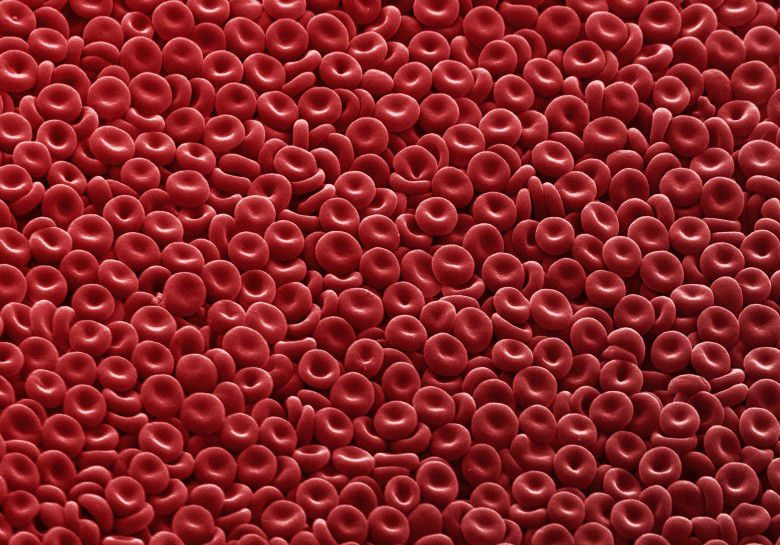

Already. Because human blood is a special mix of salts, proteins, cells and platelets perfectly organized to transport oxygen and nutrients through the body: our network of veins is a real transport infrastructure (on average 160km long per subject) through which the blood takes away garbage from the kidneys, transports antibodies and hormones; when there is a wound, the blood forms a film on it and allows healing. One of its key components, hemoglobin, is so important to life that you can find it in virtually any kind of living thing.

Since 1600 attempts to replace it have included all sorts of substances: milk, beer, urine, saline solutions and more that is even better not to say. The problem remained: the huge demand for transfusions has increased, and blood is really needed for everything from surgery to cancer treatment, from transplants to accidents.

This of course leads to a conclusion: a synthetic blood substitute would be a real godsend, even economically. An estimate says that the synthetic blood market could grow to 16 billion euros within the first 5 years of marketing this product. Almost 140 years after Dr. Howe's experiments, there is still no definitive solution to this biological puzzle.

Is there no solution?

In rapid succession what are considered the milestones in this path: 1660: first transfusion experiments with substances of all sorts. 1795: first human blood transfusion on a human. 1880: awareness of the non-existence of surrogates other than blood for a transfusion. 1966: biochemist Leland Clark demonstrates the oxygen-carrying capabilities of perfluorocarbons (PFCs), albeit with an efficiency enormously lower than that of hemoglobin. 70s-80s: tests with the use of perfluorocarbons, with verification of serious side effects. No such compound has ever won Food and Drug Administration approval. 2001: hemopure, developed by the biopharmaceutical company Biopure Corporation is the only synthetic blood approved for sale in the world (in South Africa). The drug presents high risks of heart attack, and in countries other than South Africa it is used only in desperate situations (for example in cases of refusal of transfusions for religious reasons).

The situation today

“This field was virtually obscure until recently. Now there is a glimmer of hope."

Dr. Dipanjan Pan, professor of bioengineering at the University of Illinois.

Today researchers are "armed" with much more knowledge in materials engineering, nanotechnology and blood cell biology, and they have a new strategy (right or wrong we will see): blood does not have to be perfect like real blood to have a value, and it doesn't have to be as complex as the real thing to do what you need.

For this reason they focused on creating products to be used in cases where a traditional transfusion is impossible: underdeveloped countries, ships, space stations or (in the future) Martian surface.

Erythromer, emergency blood powder

This philosophy led to the birth of Erythromer, an artificial blood cell with a particular "donut" shape that contains a nanometric-sized container with purified hemoglobin. Unlike traditional donated blood, Erythromer can be frozen, stored for a long time at room temperature and used on patients of any blood type. According to the intentions of its creators, it is possible to keep a container with Erythromer powder and in case of emergency add water to obtain "emergency blood" to keep patients alive on the journey by ambulance to the hospital.

In other words, it is not real blood, it does not have the capabilities of real blood, but it does a necessary job for a limited time, and in this it is very useful.

The tests on mice were completely successful and tests on rabbits are now underway: before tests on humans, tests will be necessary on larger animals and subsequently on primates.

Synthoplate

Other laboratories have focused on imitating the functions of platelets, which are necessary to avoid bleeding out in the event of an accident. Materials engineer Erin Lavik is developing a synthetic polymer nanostructure that “works” with platelets to accelerate and improve their performance.

In 2016, State University's Sen Gupta co-founded biotechnology startup Haima Therapeutics, which developed a platelet surrogate, Synthoplate, currently undergoing animal testing. Sen Gupta hopes that safety and toxicity assessments will enable his creation to get the go-ahead from the FDA in two to three years.